EPISODE TRANSCRIPTS

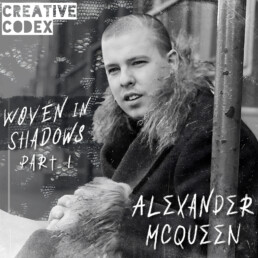

44: Alexander McQueen • Woven in Shadows (Part 1)

Have you ever been to an event where you can feel the energy of the room? Where the place just seems to vibrate with anticipation? And where every single person is fully tuned in to the moment? These kinds of experiences are rare but their rawness can provide us with something life changing—a communal moment of euphoria.

This is the type of mood which the fashion designer, Alexander McQueen, summoned in his fashion shows. His aim was to seize your attention—and show you something magnificent. To take something ugly and transform it into something beautiful, to take something beautiful and subvert it in a way you’ve never seen before. McQueen once said:

“I don’t see the point in doing anything that doesn’t create an emotion—good or bad. If you’re disgusted, at least that’s an emotion. If you walk away and you forgot everything you saw then I haven’t done my job properly.”

February 27th, 1997

The enormous hall is dark and packed tight with people—sitting and standing shoulder to shoulder. Tickets have been sold out for weeks, but that hasn’t stopped college students from forcing their way in through barricades—clamoring for a view of this highly anticipated spectacle: Alexander McQueen’s new collection.

The venue is London’s Borough Market—not your traditional sterile catwalk. The floor is hard grey cement and there are no raised platforms for the models, no separation between the show and the audience. The only indication this is a fashion event is the long rectangle which the crowd, made of hundreds of people, has formed themselves into in the center of the space—where McQueen’s models will walk. But even that has been subverted by the spilt beer and cigarette butts that litter the floor at the feet of the anxious mass.

Strobe lights flash through clouds of smoke against the back-wall, which is made of forty foot high perforated corrugated iron, making it appear to be shot through with bullet holes. Half of the audience made up of haute couture fashionistas, who no doubt feel out of place.

“You know it’s nice to show them the rough part of London and make them a bit scared and look over their shoulder once in a while. For me the reason people come to London is to see the real London, not to see a make believe London.”

A few feet from the audience, there are two abandoned cars surrounded by flaming canisters, the cars flank the opening where the models are set to emerge.

McQueen has titled the show: It’s A Jungle Out There. The music kicks in—and the show begins.

Models begin to storm out onto the cement—one at a time. They look like wild animals—with messy and frizzy hair that has been styled outward and upward—give their hair the appearance of fur.

One model, Stella Tennant, in a slim knee cut black leather dress makes her way into the spotlight. Her black leather gloves extend all the way up to her shoulders, and the dress’s v-shaped décolletage bares her chest.

Her expression is a look of ferocity, with black eye make up resembling a gazelle, the lower half of her face is covered by a large metal ring with dangling chains. Resembling something from a post-apocalyptic movie.

As she arrives in front of the audience, she turns on her high heels, and pauses with a hand on her hip. There is a floral pattern cut into her black leather dress that runs up the front, but it’s not lined with fabric—the flowers show through to the pale color of her flesh underneath.

She squares up and shoots out her hands to the side, flashing these sharp metal spikes near her fingers, like brass knuckle blades. She walks back as the next animal-woman passes her.

This is the model, Debra Shaw. She lurks through the shadows in similar black gazelle makeup with one pure white eye—giving an otherworldly touch. She’s wearing a waist length brown animal hide jacket, which is cut tight around her waist. You can see her prominent collarbone and bare breasts in the jacket’s low neckline—the deep brown hue of her skin fuses into the jacket itself. The graceful movements of her legs contrast in a startling way, she is wearing skin tight jeans, which have been severely acid washed, making them mostly white with organic splotches of blue.

But the final detail to the look is what distinctly makes this a McQueen piece—the shoulders of the jacket protrude upward at an aggressive angle, like bent elbows or the peaks of wings, and from both protrusions emerge 18 inch black horns, which curve behind and over her head.

What’s going on here?

In an interview around this time, for a BBC documentary, McQueen says this about the show…

“The idea is this wildebeest has eaten a really lovely blonde girl, and she’s trying to get out.”

“The whole show, really, was about the Thomson Gazelle, it’s a poor little critter. The markings are lovely—with these dark eyes, the white of the belly, the tan, and of course the horns. But it is in the food chain of Africa—as soon as it’s born, it’s dead. You’ll be lucky if it lasts. And that’s how I see human life, in the same way. You know, we can all be discarded quite easily. And nothing depicts it more honestly than the way animals are. And I was trying to also say, the fragility of the designers time in the press—you’re there, you’re gone. It’s a jungle out there.”

This is not just a fashion show—it’s a work of art. It’s an artist’s statement.

The aggressive demeanor of the models gives the impression that these animal-women are not potential victims on the food chain, but rather apex-predators on the prowl. If this were a horror movie, the audience in attendance would soon be the victims of a bloody feeding frenzy.

One audience member describes the show afterward as a “vision of urban chaos…both on and off the catwalk.”

Students from Central Saint Martins have forced their way in through gaps in the iron walls, and one of them kicks over a fire canister towards one of the cars. Journalist Grace Bradberry said “The audience screamed and clapped as a fire broke out in a van.”

McQueen is yelling backstage for the show to continue uninterrupted and it does. The audience has no idea that the fire is not a planned part of the spectacle.

In total, McQueen shows 100 pieces at the event and critics call it a rousing success. A welcome change from the disastrous critical reviews of his last show. In an interview afterward, McQueen expresses a certain kinship to the Thomson Gazelles which inspired his designs that night. He admits:

“Someone’s chasing after me all the time, and if I’m caught, they’ll pull me down…”

Welcome to Creative Codex, I am your host, MJDorian.

This is Part 1 of a special series about the fashion designer, Alexander McQueen.

I’d like to preface this episode by saying that this is not a series only meant for people who are into fashion or who are already familiar with McQueen’s designs. Before starting this series I didn’t know the first thing about the fashion industry. So it’s been a tremendous learning experience. This series, like all episodes of Creative Codex is a sonic portrait of a creative genius. A special human that gave something substantial and consequential to the world in the short time that they existed on it. So if you are beginning this series with no prior knowledge about fashion—good—because so am I.

I’ve wanted to do a series about McQueen for a long time now, as he perfectly fits the model of a creative genius that we explore on this show. I also suspect that studying his life and work will provide us with countless insights into creativity and what the inner life of genius looks like. But there’s also these intriguing unknowns about his life which we will need to contend with.

One of the questions we will be exploring on this episode is: how does a boy from a working class family with no fashion industry connections go on to become one of the most famous and sought after designers of the 21st century? Because unlike figures like Vincent van Gogh or Emily Dickinson, who we’ve covered on the show, McQueen does achieve worldwide recognition of his creative genius—during his lifetime—a very rare feat. Throughout the series we will also explore the question: what happens along the way that leads to his tragic end?

And finally, what fueled his work and designs? Alexander McQueen is known to have created some of the most iconic fashion shows and designs in modern fashion. What were the driving forces of all this creative genius?

It’s time to find out.

This is Codex 44: Alexander McQueen • Woven in Shadows (Part 1)

Let’s begin…

Chapter One: Shadows of Youth

Cautionary Note: There will be mentions of domestic violence and sexual abuse later in this chapter. Listener discretion is advised.

Alexander McQueen grabs a crayon from his sister’s room and shuffles over to a bare wall in his parent’s home. The crayon touches the surface, and he begins scribbling. This is his first official artwork: a picture of Cinderella ‘with a tiny waist and a huge gown.’ Alexander is only three years old at this time, but his mother, Joyce, is already noticing there is something peculiar about him.

One time, she dresses him up to go to the store in trousers and a parka and little Lee, as he is known around the house, says “Mum, I can’t wear this.” She asks him “Why not?” to which he replies “It doesn’t go.” Looking back at his childhood, McQueen admits “I was absorbed early on by the style of people, by how they expressed themselves through what they wear.”

Joyce McQueen gave birth to Lee Alexander McQueen on March 17th, 1969 at Lewisham Hospital in southeast London. Little Lee was born weighing only five pounds and ten ounces, but as the doctors saw he fed well, they chose not to place him in an incubator. Joyce brought Lee home shortly after to a full house—he was the youngest of six children.

Lee’s father, Ron, was the sole breadwinner of the family—working day and night as a cab driver on London’s streets. This meant that they didn’t have much, but they were always cared for—Joyce made sure of that.

The house was a modern working-class home with a fitted patterned carpet complete with floral sofas with wooden arms. The kids slept three to a bed, which helped keep everyone warm in the wintertime. Due to power cuts in the 1970s, the house was often under a three day weekly limit for electricity consumption. Some of the kids left school and started working at fifteen, when money was tight, Joyce would work as well, cleaning houses.

Some years were harder than others though. Lee’s brother, Michael McQueen said “My dad had a breakdown in 1969, just as my mum gave birth. He was working too hard, a lot of hours as a lorry driver with six children, too many really.”

Lee’s brother Tony recalls the time, saying “Dad had a nervous breakdown and he went into a mental institution for two years…My mum got someone round and they institutionalized him. It was a difficult period for us.”

Although Lee is only a baby at this time, the family character trait of an obsessive work ethic will carry through into his adulthood. Something he no doubt picked up from his father, Ron. After Ron returns from the mental institution, he goes right back to work.

In the biography titled Alexander McQueen, Blood Beneath the Skin, the author writes:

“It’s difficult to know the exact effect of Ronald’s breakdown on his youngest son…There is no doubt, however, that in an effort to comfort both their infant son and herself, Joyce lavished increased levels of love on Lee and, as a result, the bond between them intensified.

As a little boy, Lee had a beautiful blond head of curls, and photographs taken at the time show him to be an angelic-looking child. Michael McQueen admits “He had preferential treatment from my mother but not my dad; he was a bit Neanderthal because of his hard upbringing.”

By all accounts, Lee was a boisterous and mischievous child. At the age of 11 he was sent to an all boys’ comprehensive school called Rokeby. At the end of the terms, the teachers wrote evaluations in his report card. Here is Lee’s mother, Joyce, from the documentary Cutting Up Rough—she saved his report cards and shares some of these notes that teacher’s wrote:

Another comment says he would improve if he could just “begin to act like a comprehensive pupil instead of fooling about all the time” and that his “class behavior interferes with his work.”

Reports from two years later show improvement in his grades, but his behavior continues to be a point of contention, the French teacher writes that he needs “constant goading to get his attention down to his work. He too often daydreams and enjoys chatting.” Finally, the head of the lower school summarizes the report by saying “mixed bag—he has the ability but seems to choose when to apply it.”

But there is one subject in which Lee never has issues and always excels: art.

In the book, Alexander McQueen, Blood Beneath the Skin, the author writes:

“Lee started to read books about fashion from the age of twelve. “I followed designer’s careers,” he said later. “I knew Giorgio Armani was a window-dresser, Ungaro was a tailor…I always knew I would be something in fashion. I didn’t know how big, but I always knew I’d be something.

His friends noticed Lee’s passion for drawing. “He just seemed to be sketching, drawing all the time,” said Jason Meakin. “I never thought he would be famous, but I always remember him drawing dresses.” Peter Bowes recalls that in school Lee would always carry a little book around with him. Instead off listening to the teacher or doing the work assigned in a particular class, Lee would bring out his sketchbook and a clutch of pencils and draw.

“It was full of nutters,” McQueen said later about Rokeby. “I didn’t learn a thing. I just drew clothes in class.” One day Lee showed Peter some of his sketches, drawings of the female form. Peter recalls “He was drawing clothes, people, figures, he knew how the female form worked, but it was nothing rude. He lived in the art department and his work was always superb.”

Due to his working class English upbringing, Lee developed a certain toughness in his adolescence, but under the surface, he was a sensitive art kid with deep-seated vulnerabilities.

Lee started being self conscious about his physical appearance from an early age. Once when he was a young boy he slipped off a short wall in his backyard, hitting his teeth. His brother, Tony, admits “He was always self-conscious about his teeth after that,” and his childhood friend, Peter Bowes says “I remember he had an accident when he was younger and lost his milk teeth and the others came through damaged or twisted. So he had the buck front teeth, one of the things that would give him a reason to be humiliated and picked on. He was called ‘goofy’ and things like that.”

And Alice Smith, who was a friend of Lee’s in his adult years, adds even more color to the portrait of his youth saying “He was this little fat boy from the East End with bad teeth who didn’t have much to offer, but he had this one special thing, this talent, and Joyce believed in him. He told me once that she had said to him, ‘Whatever you want to do, do it,’ He was adored; they had a special relationship, it was a mutual adoration.”

Though aside from these superficial concerns about his appearance, there are these occasional hints of a very real darkness in his childhood.

His sister, Janet, married a man named Terence Hulyer in 1975. She knew he had a bad temper, but she was twenty one and desperate to move out of the family home. Lee was only six years old at the time of their marriage, in the years that followed, he would often be left in their care while his parents were at work.

Many times, Lee witnessed Terence fly into a rage about something Janet said or did and he would beat her. One time he beat her because she ordered a cup of tea from a waitress in a café without letting him speak first. This is the broken logic of a serial abuser. Janet had two sons with him, but she admitted to author, Andrew Wilson, that she miscarried two babies because of the abuse from Terence Hulyer.

In an interview with Independent Fashion Magazine, in 1999, McQueen states “I was this young boy and I saw this man with his hands round my sister’s neck. I was just standing there with her two children beside me.”

In some of his later fashion shows, McQueen would be accused by the press of being misogynistic, a label which particularly offended him. In October 1997, he told Vogue “I’ve seen a woman get nearly beaten to death by her husband. I know what misogyny is! I hate this thing about fragility and making women feel naïve…I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.”

This calls to mind the scenes of his show, It’s a Jungle Out There, which we opened this episode with. The one with the animal-women storming the Borough Market asphalt. McQueen’s fashion shows are woven from the shadows of his private traumas and memories.

In May of 1985, Janet’s husband, Terence, suffered a massive heart attack while driving his car, he lost consciousness as the car careened into a nearby house. He died in the hospital. His death must have left a complicated mixture of emotions in its wake.

Roughly 20 years later, Lee told Janet a secret he had been holding onto for a long time: Terence had sexually abused Lee throughout his childhood. It began when Lee was between nine and ten years old. Janet was stunned and overwhelmed by guilt—she had known nothing about the abuse. She asked if he blamed her for it, he said no. After that brief conversation, they never spoke of it again, Janet didn’t want to pry with more questions and she felt sickened by what her first husband had done.

Lee never told anyone the full details of the abuse, but throughout his adult life, friends and partners remember Lee only talking about it in passing moments—and rarely going into details or about how long he endured it. It was clearly a trauma he carried his entire life.

The book, Alexander McQueen, Blood Beneath the Skin states:

“Rebecca Barton, a close friend of Lee’s from St. Martins recalls “Lee told me he had been sexually abused and that it massively affected him.”

Lee’s partner, Andrew Groves states “Once when we were at my flat in Green Lanes he broke down and said he had been abused.” Andrew believes that the sexual abuse contributed to McQueen’s unsettling ‘sense that someone was going to screw him over’ and an inability to trust those close to him.

Once when Lee was feeling particularly overwhelmed by a sense of darkness, he had ‘a real heart to heart’ with his boyfriend Richard Brett ‘about why he went to the dark place’ and he told him too about the sexual abuse, but again kept the exact details to himself.

“But I got the impression that some nasty stuff had happened to him when he was a boy,” said Richard. Lee also confided in Isabella Blow and her husband, Detmar. Detmar said “He was hurt and angry and said that it had robbed him of his innocence. I thought it brought a darkness into his soul.”

It’s such a tragic element of McQueen’s life, and he was understandably guarded about speaking about it. It’s possible that the only person who truly knew the whole story was his mother—with whom he kept a very close relationship his entire life—someone who he would have felt he could confide in as an adult.

Back in middle school, Lee wasn’t any kind of outsider, he made friends easily. His childhood friend, Peter Bowes says that Lee was ‘quite a tough guy—he wasn’t scared of people.’ And although his nickname around the school was Queeny or ‘queer boy Queeny’, it was just one of those stupid nicknames kids use to taunt each other with—his friends didn’t actually think he was gay.

His childhood friend, Jason, remembers he and Lee would hang out in the back of an engineering firm near the River Lea after school and on weekends. Lee kissed a string of local girls back there, Sharon, Maria, and Tracy. Jason recalls “I don’t want to go into details but I know three girls who Lee kissed and cuddled. One of them went a bit further, not full sex. It was messing around. As far as being gay, no way—that was a big surprise.”

Peter also recalls that Lee didn’t quite know where he was going in life, but he had this sense of yearning to do something artistic and creative. He had an ambitious imagination, and his mother’s love of tracing their family tree rubbed off on him in beneficial ways.

Peter states “He was fascinated by Alexander the Great and he claimed to have found in his family a link back to him.” The idea planted it’s seed well in him—that in his very blood there already existed greatness, all that was left to do was to bring it out into the world.

But even in school, there were also traces of darkness. The book, Blood Beneath the Skin recounts:

“Towards the end of his time at Rokeby, Lee started to suffer from sudden attacks of frustration and anger. “I wouldn’t say he was bipolar but he had his ups and downs with moods,” said Peter. “He had a bit of a temper on him as well. I remember in certain lessons he would be chatting and he’d get told off. He would erupt and kick off and get thrown out or put into detention.

None of his friends at school could have realized it, but Lee later claimed he was suffering yet more sexual abuse during this period, this time at the hands of a teacher.

Again Lee kept the abuse to himself, only telling his sisters later in life. Years later, when Jacqui learnt of the two counts of abuse suffered by her brother everything began to make sense: the anger had to come out somehow and Lee later expressed it through his work…”

McQueen’s collections are woven in the shadows of his traumas and memories. And the two go hand in hand, it’s like to understand his designs one must understand his personal history and to understand his personal history one must look to his designs.

When McQueen was developing as a fashion designer, the journalist, Vassi Chamberlain, asked him about his fascination with birds. McQueen said he envied birds because they were free.

Chamberlain asked him “Free from what?” McQueen responded “The abuse…mental, physical.” She asked him a followup question and he refused to elaborate.

INTERMISSION

And now it’s time for a brief intermission.

If you enjoy what we do here on Creative Codex I have one simple request: please share it with somebody—a friend, a coworker, a teacher—your neighborhood cat [meow]—anyone who you think will dig it. We’re not like one of these million dollar podcasts with celebrity guests, corporate funding, and an advertising budget. This show only grows because of you.

And if you already shared it and would like to do a little more to help, please rate the show on Spotify or leave a review on Apple Podcasts. We are so close to crossing the 2,000 reviews mark on Spotify—you can help get us there. And I thank you in advance for all of that.

At this point of the episode, in most podcasts, you’d hear an ad for caffeinated hot dogs, Chernobyl Brand Spring Water, or A.I. relationship counseling to help with your A.I. girlfriend. But not on Creative Codex.

Instead I’m going to play you a preview of my Kurt Cobain series. As I was working on this McQueen episode I started noticing some odd similarities between Kurt’s life and Lee’s life. For example: both of their careers take off in the 90’s, both of them spend their youth feeling like outsiders who don’t fit in, both have a strong spirit of boyish anarchy in their personality, both of them are creative geniuses, and both pursue their dream of becoming famous for their creative talent—and they reach it.

I imagine Kurt and Lee would have got on pretty well. They probably would have snorted a line together—it was the 90’s after all.

Last year I released a special four part series about Kurt as a thank you to my Patreon supporters. It’s part of something I call the Limited Release Series. These are episodes only available for supporters in the $5 and up tiers. Keep in mind, this will never appear in the main podcast feed, so if you’d like to hear all four hours of the Kurt Cobain episodes head on over to patreon.com/mjdorian, and you can find it there.

Here is a preview of my Limited Release Series about Kurt Cobain, singer, songwriter, and guitarist of the band Nirvana.

That was a preview of my Limited Release Series about Kurt Cobain. If you’d like to become a supporter of Creative Codex and gain access to these exclusives, including Carl Jung’s Red Book Reading series, simply head on over to patreon.com/mjdorian.

I thank you in advance for that. And now, back to Codex 44: Alexander McQueen • Woven in Shadows (Part 1)

Chapter 2: Clothes as a Weapon / Needle & Thread

It’s obvious to everyone in the McQueen household that Lee has a passion for clothing and creativity. After he graduates high school, he even makes custom skirts for his sisters, in essence, these are his first commissions. His mother knows that he isn’t cut out for bricklaying like one of his brothers or taxi driving like his father. He later tells an interviewer “It’s not heard of to be a fine artist in an east London family. But I always had the mentality that I only had one life and I was going to do what I wanted to.”

In an interview for the documentary series, Cutting Up Rough, Lee’s sister Janet and then his mother Joyce mention this:

[cue 13:42, Cutting Up Rough. Janet: “I did often wonder when he’d get a job, what we’d call a proper job.” Joyce: “He was different right from the beginning, he was different right from when he was young.”]

Lee wants to learn everything he can about fashion, he acquires a copy of a book called McDowell’s Directory of Twentieth Century Fashion. For the next few years, this book is like a bible to him. He reads it and studies it end to end. It functions like an encyclopedia of fashion history, with entries arranged alphabetically, spanning international fashion and biographies of the twentieth century’s great designers.

The book, Blood Beneath the Skin further describes the book:

“In its opening chapter—titled “Clothes as a Weapon”—the author, the renowned journalist Colin McDowell, outlines the importance of fashion and its place in history. The words struck a chord with the young McQueen. “The more remote fashionable people become, the more powerful and awe-inspiring they seem to the unfashionable majority,” he wrote. “In the past this meant that clothes became not only the trappings of power, but part of the exercise of power itself.”

Lee read about the connection between fashion and the visual arts, how Dior, Chanel and Schiaparelli “were all closely involved with artists, writers and intellectuals.” McDowell went on to explain why fashion is so often wrongly regarded as a somewhat frivolous discipline.

The first reason, he said, was visual—unlike objects created by furniture and interior designers, a jacket or a dress “loses a great deal of its point when hanging in a wardrobe. It becomes a rounded and convincing creation only when there is a body inside it.” The other reason why fashion is denigrated is because for a long time it has been seen as the “domain of women…as objects, frequently using dress as a bait and as a reward.

An interest in clothing has become a symbol of suppression. The ‘little woman’ is bought with an expensive dress and by wearing it she feeds a man’s ego. She is telling her friends, by her expensive appearance, how rich and powerful he is to be able to buy and possess such a beautifully caparisoned object.”

These philosophical arguments about fashion’s role in society without-a-doubt influence McQueen, and plant the seeds in his imagination which will eventually develop into his own fashion ethos. The women who McQueen envisions dressing in his pieces are not objects or victims. They are independent and potentially dangerous subjects—the clothes they will wear are not decorative, they will be powerful.

But as a young man just out of school, this vision is still in its infant stages. Only hints of it will show through in Lee’s illustrations. For example, around this time, Lee often babysits his sister Janet’s two sons. They recall that he’s always drawing—when he isn’t chasing them around the house, playing the part of a hunter and laughing maniacally. The sketches include nude men and women, monsters, feathers and birds. The kids loved Lee, they watch horror movies together and he styles their hair.

The possibility of working in fashion fuels his daydreams, but the reality of his situation is hard to shake: how can a working class kid from east London with no connections to the industry ever make it?

His luck finally takes a turn one day in 1986. The book, Blood Beneath the Skin, states:

“According to McQueen, one afternoon in 1986 he is at home in Biggerstaff Road when he sees a program on television about how the art of tailoring is in danger of dying out. There is, said the report, a shortage of apprentice tailors on Savile Row and so his mother says to him, ‘Why don’t you go down there, give it a go?’

(Later) speaking in 1997, Joyce recalls, ‘He always wanted to be a designer, he always has, but when he left school he wasn’t sure what to do. Quite a few of the family were involved in tailoring so I just said to him, ‘You know, why don’t you go and try?’

Spurred on by his mother, Lee takes the tube to Bond Street and walks through the smart streets of Mayfair until he comes to 30 Savile Row, the headquarters of Anderson & Sheppard. McQueen said “I hardly had any qualifications when I left school, so I thought the best way to do it was to learn the construction of clothes properly and go from there.”

Anderson & Sheppard was founded in 1906 by Per Gustaf Anderson, a protégé of Frederick Scholte, who was famous for developing the English drape for the Duke of Windsor, and the trouser cutter Sidney Horatio Sheppard.

‘A Scholte coat was roomy over the chest and shoulder blades, resulting in a conspicuous but graceful drape,’ wrote one style commentator, ‘the fabric not flawlessly smooth and fitted by gently descending from the collarbone in soft vertical ripples. The upper sleeves, too, were generous, allowing for a broad range of motion, but the armholes, cut high and small, held the coat in place, keeping its collar from separating from the wearer’s neck when he raised his arms. The shoulders remained unpadded, left to slope along the natural lines of the wearer.’

That day in 1986, Lee, dresses in jeans and a baggy top and looking more than a little disheveled, walks through the heavy double doors, across the herringbone floor and into the mahogany-paneled room. The contrast between the interior of Biggerstaff Road—his home—and the inside of the tall Neoclassical building could not be more striking, but the overpowering aroma of privilege does not intimidate him.

‘He wasn’t a timid person,’ says John Hitchcock, who started working for the tailor in 1963. Lee tells the besuited man standing by the long table piled high with expensive tweeds that he is interested in becoming an apprentice. A moment or so later […] the head salesman […] comes down to interview him. The handsome older man, with his aquiline nose and head of silver hair, is an astute judge of character, and after talking with the seventeen-year-old boy, Halsey offers him a job.

The position is not well paid and McQueen earns only a few thousand pounds a year, probably the equivalent of three Anderson & Sheppard suits. ‘It was obvious when he first came he did not know anything, he was a blank canvas,’ said Hitchcock, who worked as a cutter in the mid-to late eighties.”

On his first day, Lee is given a thimble, a line of thread, and a scrap of fabric. He is assigned a master tailor as his mentor, a strict Irishman who is regarded as one of the best makers of suit jackets in the business. Lee is expected to work eight hour days, arriving 8:30am and finishing work at 5:00pm.

John Hitchcock says “New apprentices have to practice doing this [padding] stitch, and they have to keep doing it. An apprentice will do thousands and thousands of these stitches and, although it becomes very boring, they have to learn. After doing that for a week, the apprentice might then move on to learn about inside padding, how to canvas the jacket, put the pockets in, and the flaps. It normally takes about two years to learn the simple tasks.”

In later years, McQueen speaks fondly about his time at Anderson & Sheppard, crediting them with giving him a strong foundational understanding of working with fabric. He says “It was like Dickens, sitting cross-legged on a bench and padding lapels and sewing all day—it was nice.” But he also admits that the old world social atmosphere of the workplace made him feel out of place, saying

“It was a weird time for me, because at sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, I was going through the situation of coming to terms with my sexuality and I was surrounded by heterosexuals and quite a few homophobic people and every day there would be some sort of remark. Downstairs on the shop floor was quite gay but upstairs was full of people from Southend and south London, just like any other apprentice trade, full of lads being laddish. So I was trying to keep my mouth shut most of the time because I’ve got quite a big mouth.”

In the documentary, Cutting Up Rough, McQueen states:

He tends to keep to himself, though he does introduce some of the other workers to house music, a scene he’s really into at the time. One of his coworkers said “I didn’t know he was gay, he never talked about it. He did behave in a slightly strange way, but I didn’t put it down to him being gay.”

The book, Blood Beneath the Skin states:

“The goal of every new apprentice tailor is to make what is called a ‘forward’—a jacket that is nearly complete and ready for a first fitting on a customer. Normally, it would take between four and five years for a new person to learn the necessary skills, but McQueen does this in two. ‘Con taught him well,’ said Hitchcock. ‘Lee was very keen to learn and he had a natural ability.’”

The environment of Anderson & Sheppard is very prim and proper, at times they are even commissioned to work on the clothing of British royalty. But under the surface of Lee’s composed exterior there still exists a touch of boyish anarchy.

Lee later says in an interview “When you first start you’re there for three months solid just padding lapels. So you get bored and then you do a bit of scribbling inside the jacket, and you might scrawl an obscenity—like a sixteen-year-old does when it’s bored. But it was just a passing phase.” During another television interview he admits that one time, he happened to be working on Prince Charles’ jacket, and so he drew a big willy inside of it and scrawled the letters C-U-N-T where no one would see.

When news of this gets out, the shop recalls the Prince’s suits, and opens the lining and searches the lapels to find the marks in question—to no luck. Was Lee joking or had the marks been made with a grease pencil and rubbed off?

Andrew Groves, one of Lee’s boyfriends in later years said this about his personality “Whatever he was doing he could not help but subvert it. He always wanted to undermine the idea of authority and the establishment.”

Lee’s tenure at Anderson & Sheppard lasts two years. Not because of some predetermined timeline, but because of a certain incident. In the last week, one of the supervisors pulls him aside and tells him his tardiness is becoming a problem—he’s even been missing entire days. Hitchcock recalls “I told him that he was putting everyone else behind, but he got a bit shirty and left. We didn’t sack him, he just walked out. Later we learnt that his mum had been ill, but if he had told us we would have given him a week off.”

But despite these possible personal reasons, there’s also the fact that Lee is a creative at heart, and although working on the nuances of the same jacket style for hours might be fine work for others, his heart was elsewhere.

About this he said:

[cue Cutting Up Rough, roughly 12:00 “A single breasted jackets a single breasted jacket…I wanted to put lapels back of the neck, up the ass, and everywhere else.]

The next few years after Anderson & Sheppard are a whirlwind of freelance work in various clothing shops and fashion firms. Shortly after Anderson & Sheppard, Lee gets hired as a tailoring apprentice by a shop further down Savile Row called Gieves & Hawkes. One of the owners later tells a journalist:

[cue Cutting Up Rough, roughly 11:30:

“I certainly remember him working with us, and sadly we lost his talent—no way were we going to keep him—his mind and nature were inquisitive, never short of asking questions. Why this, why that, why put a cut in a coat here rather than there, to create a chest suppression in a waist? All this was very evident from the way he worked and the way he talked.”]

Lee leaves Gieves & Hawkes one year later.

Following that job, Lee takes on any work he can get, including working at Reflections—known to locals as the roughest pub in the East End. According to one of the regulars “When that door locked you got scared. There were fights, sex, everything.” He remembers Lee walking around collecting glasses, avoiding making eye contact with people.

Around this time he also freelances for a theatrical costume company, working on productions such as Les Miserables and Miss Saigon. When Lee is later asked why he left the job he says “I was surrounded by complete queens, and I hate the theatre anyway.” But those closest to him, such as one of his boyfriends, Andrew Groves, believe that experiencing the theatrical spectacles firsthand inspired McQueen toward similar performance elements in his fashion shows—the need to leave an impression—a way to really give the audience something to talk about.

After his stint in theatre, Lee tracks down the Japanese designer, Koji Tatsuno, who is based in London, and visits his offices in the hopes of securing a job in his design firm. Tatsuno is an unconventional designer, lacking formal training, with his own established aesthetic. He’s intrigued by Lee, especially the prospect of subverting his traditional Savile Row training toward new modern designs. Lee boldly tells Tatsuno that he can ‘cut a coat’ better than any tailor he currently has.

Tatsuno is quoted as saying “My first impression of him was that he was a bit weird. I could tell he was attracted to the dark side of beauty, and it was something I could relate to as well.”

Tatsuno hires McQueen as an intern. Although the experience only lasts less than a year, it has a tremendous influence on McQueen. Tatsuno is the first designer Lee works with who doesn’t measure and cut fabrics flat on a table, but rather uses a more intuitive approach—wrapping the model in the fabric and cutting and shaping the form in three dimensions. This is an approach which McQueen would master in the coming years, and it becomes a signature skill of his.

Koji Tatsuno’s business goes bankrupt in 1989, and Lee is out of work again. He asks a colleague if she knows of any other brands where he could get work, and she recommends him to John McKitterick, head designer of the street fashion brand Red or Dead. This job will prove pivotal for Lee’s career in many ways. It’s at Red or Dead that he sees the possibility of more experimental catwalk shows. For example, the Spacebaby collection of 1990, which was inspired by NASA’s space shuttle missions, and featured white and transparent plastic outfits, trippy operatic sci fi music, and models wearing metallic head pieces that looked like atoms.

In the documentary, McQueen, McKitterick recalls Lee being a bit surprised by the concept, that a fashion company could put on a catwalk show inspired by themes that had nothing to do with fashion. The little seed this planted in his imagination would take root quickly, and influence him for the rest of his career.

In the spring of 1990, Lee heads to Milan, Italy, and through a stroke of both luck and serendipity, he lands a job as a pattern cutter for the prestigious designer, Romeo Gigli. Lee would know Gigli from his popularity in fashion of the 1980’s but also from his entry in one of Lee’s favorite books: McDowell’s Directory of Twentieth Century Fashion. Which states:

“His unstructured clothes with their emphasis on an elongated silhouette soon made him stand out from the mainstream Italian fashion…Gigli’s shows have become cult affairs and his clothes are eagerly bought by wealthy young women world-wide. His designs are a synthesis of London post-punk street fashion and Japanese avant-garde style presented with Italian refinement and color to produce clothes of extreme subtlety and elegance…Many fashion experts consider him the most important designer to have appeared in the eighties.”

Seeing the inner workings of Romeo Gigli’s fashion house becomes invaluable to Lee’s development as a designer. He sees what the inner architecture of a high fashion workshop looks like, who does what, how collections are planned and scheduled, and where funding for shows comes from. He also sees the editors of Paris magazines flip their wigs for Gigli’s catwalk shows, his designs have the ability to elicit emotional reactions. All of this—this is what McQueen wants—this is who he wants to be.

And Lee is also learning about publicity and public perception from watching Gigli’s operation. Looking back at that time he later said

“Gigli had all this attention and I wanted to know why. It had very little to do with the clothes and more to do with him as a person. And that’s fundamentally true of anybody. Any interest in the clothes is secondary to the interest in the designer. You need to know that you’re a good designer as well, though. You can’t give that sort of bullshit without having a back-up. If you can’t design, what’s the point of generating all that hype in the first place?”

In Gigli’s workshop, Lee becomes quick friends with a fellow design assistant named Carmen. They first connect when she offers him an aspirin, after noticing he’s having tooth pain. Carmen later says this about Lee:

“When he looked at you he had piercing blue eyes. He was shy and had a kind heart. He was a good person. I got the impression he was not out of the closet. He wore loose jeans and loose shirts, a pocket chain, he looked like a street guy. And his teeth were in bad shape, he was self-conscious about that. And he had a tooth missing—you wouldn’t notice if he spoke, but if he threw his head back and laughed you could see it.”

They sit next to each other all day, often sketching out ideas for forthcoming collections on vellum paper. Lee sometimes sketches bizarre images and passes them to Carmen, signed ‘with love, Lee’—hybrid figures, half animal-half human, mermaids, veiled faces, breasts adorned with metallic cones, mythical birds, and arrows through model’s torsos.

She later says “The collections at the time were very Pre-Raphaelite, all about beautiful women, and here was this guy sketching monsters. I thought, ‘What is going on with this guy?’”

Lee makes other friends in Milan too. He lives in a flat shared by other colleagues working at Gigli’s office. One night they’re having dinner and the topic of Milan nightlife comes up. Lee ‘rattles off’ a list of gay clubs, the size and scope of which only a connoisseur would know. The friends at the table share a look, no one would have guessed this shy Brit was actually a party animal.

Another friend, Simon Ungless, recalls Lee regaling him with tales of debauchery in Italy, saying “He talked about doing things that were absolutely physically impossible. Really ridiculous things about being in some kind of hoist and being lowered onto way too many men at once.”

Lee’s stint in Italy with Gigli comes to an abrupt end in the summer of 1990, after the company implodes due to a breakdown in the personal relationship between Gigli and his business partner. Lee heads back to London, and back to work for the John McKitterick, the former head of Red or Dead. He tells McKitterrick that his ultimate dream is to be a designer. McKitterrick advises him that he can ‘learn it by working with someone else, but the best way is to go to school.’

McKitterrick tells Lee he should apply for Central Saint Martins—a world famous fashion and arts school located in Soho, London. Lee had heard about this university many times, but never thought he could afford to take the courses. He was living on low income public assistance checks at this time, where would he find the money? Perhaps he could start by working there in some capacity?

Coincidentally, McKitterrick is teaching a Masters course at Central St. Martins. He gives Lee the contact to the founder and director of the Masters course, Bobby Hillson, and he insists that he go and see her immediately.

On the next Creative Codex:

McQueen enrolls in Central St. Martins fashion school. It’s there that he creates his first collection of clothes infamously inspired by the Jack the Ripper murders. It’s also through St. Martins that he meets a woman who will help propel him into the spotlight: Isabella Blow. “The pieces moved past me and they moved in a way I’ve never seen. They were modern, they were classical, and I wanted them…I just thought—this is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.” McQueen’s following collections draw international attention and controversy. Can he handle the pressure? All this and more on Alexander McQueen • Woven in Shadows Part 2.

PATREON

Become a patron of the show, and gain access to all the exclusive Creativity Tip episodes, as well as episode exclusives. Just click the button or head over to: https://www.patreon.com/mjdorian

Wanna buy me a coffee?

This show runs on Arabica beans. You can buy me my next cup or drop me a tip on the Creative Codex Venmo Page: https://venmo.com/code?user_id=3235189073379328069&created=1629912019.203193&printed=1