EPISODE TRANSCRIPTS

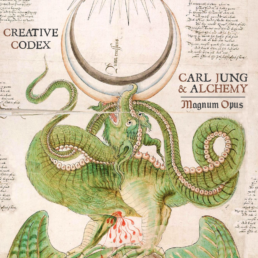

41 Jung & Alchemy • Part III: Magnum Opus

Welcome to Creative Codex, this is Part 3 of the Carl Jung and Alchemy series, I am your host, MJDorian. We’re going to start today’s episode with a story. Not just any story: a Grimm’s fairy tale, first published over 200 years ago.

The name of this old tale is: The Spirit in the Bottle. Pay close attention to the symbolism throughout, it will be important later.

Our story begins…

Chapter 4: The Spirit in the Bottle

Once upon a time, there was a poor woodcutter who toiled from early morning till late at night. When at last he had laid some money aside he said to his boy,

“Thou art my only child, I will spend the money which I have earned with the sweat of my brow on thy education; if thou learnst some honest trade thou can support me in my old age, when my limbs have grown stiff and I am obliged to stay at home.”

Then the boy went to a High School and learned diligently so that his masters praised him, and he remained there a long time. When he had worked through two years, but was still not yet perfect in everything, the little pittance which the father had given him was all spent, and the boy was obliged to return home to him.

“Ah,” said the father, sorrowfully, “I can give thee no more, and in these hard times I cannot earn a farthing more than will suffice for our daily bread.”

“Dear father,” answered the son, “do not trouble thyself about it, if it is God’s will, it will turn to my advantage. I shall soon accustom myself to it.”

That day, the father wanted to go into the forest to earn money by helping to pile wood, stack and chop it, the son said, “I will go with thee and help thee.” “Nay, my son,” said the father, “that would be hard for thee; thou art not accustomed to rough work, and will not be able to bear it, besides I have only one axe and no money left wherewith to buy another.”

“Just go to our neighbor,” answered the son, “he will lend thee his axe until I have earned one for myself.”

The father borrowed an axe of the neighbor, and next morning at break of day they went out into the forest together. The son helped his father and was quite merry and brisk about it. But when the sun was right over their heads, the father said, “We will rest, and have our dinner, and then we shall work as well again.”

The son took his bread in his hands, and said, “Rest thou, father, I am not tired; I will walk up and down a little in the forest, and look for bird’s nests.” “Oh, thou fool,” said the father, “why shouldst thou want to run about there? Afterwards thou will be tired, and no longer able to raise thy arm; stay here, and sit down beside me.”

The son, however, went into the forest, ate his bread, was very merry and peered in among the green branches to see if he could discover a bird’s nest anywhere.

So he went up and down, deeper into the dark forest, until at last he came to a great dangerous-looking oak, which certainly was already many hundreds of years old, and which five men could not have spanned. He stood still and looked at it, and thought, “Many a bird must have built its nest in that.” Then all at once it seemed to him that he heard a voice.

He listened and became aware that someone was crying in a very smothered voice, “Let me out, let me out!”

He looked around, but could discover nothing; nevertheless, he fancied that the voice came out of the ground. Then he cried, “Where art thou?”

The voice answered, “I am here, down among the roots of the oak tree. Let me out! Let me out!”

The scholar began to loosen the earth under the tree, and search among the roots, until at last he found a glass bottle in a little hollow. He lifted it up and held it against the light, and then saw a creature shaped like a frog…springing up and down in it.

“Let me out! Let me out!” it cried anew, and the scholar, thinking no evil, drew the cork out of the bottle.

Immediately a spirit ascended from it, and began to grow, and grew so fast that in a very few moments he stood before the scholar, a terrible fellow as big as half the tree by which he was standing.

“Knowest thou, what thy wages are for having let me out?”

“No,” replied the scholar fearlessly, “how should I know that?”

“Then I will tell thee—I must strangle thee for it.”

“Thou shouldst have told me that sooner,” said the scholar, “for I should then have left thee shut up, but my head shall stand fast for all thou can do; more persons than one must be consulted about that.”

“More persons here, more persons there. Thou shalt have the wages thou hast earned. Dost thou think that I was shut up there for such a long time as a favor? No, it was a punishment for me. I am the mighty Mercurius.

Whoso releases me, him must I strangle.”

The scholar answered “Softly, not so fast. I must first know that thou were shut up in that little bottle, and that thou art the right spirit. If, indeed, thou can get back in again, I will believe it, and then thou mayst do as thou wilt with me.”

The spirit said haughtily, “That is a very trifling feat.” He drew himself together, and made himself as small and slender as he had been at first, so that he crept through the same opening, and right through the neck of the bottle in again. Scarcely was he within than the scholar thrust the cork he had drawn back into the bottle, and threw it among the roots of the oak into its old place, and the spirit was betrayed.

The scholar was about to return to his father, but the spirit cried very piteously, “Ah, do let me out! Do let me out!” “No,” answered the scholar, “not a second time! He who has once tried to take my life shall not be set free by me, now that I have caught him again.”

“If thou will set me free, I will give thee so much that thou wilt have plenty all the days of thy life.”

“No,” answered the scholar, “thou wouldst cheat me as thou didst the first time.”

“Thou art playing away thine own good luck, I will do thee no harm, but will reward thee richly.”

The scholar thought, “I will venture it, perhaps he will keep his word, and anyhow, he shall not get the better of me.”

Then he took out the cork, and the spirit rose up from the bottle as he had done before, stretched himself out and became as big as a giant.

“Now thou shalt have thy reward,” said he, and handed the scholar a little bag which felt strangely like plaster in his hands, and said “If thou spreadest one end of this over a wound it will heal, and if thou rub steel or iron with the other end it will be changed into silver.”

“I must try that,” said the scholar, and went to a tree, tore off the bark with his axe, and rubbed it with one end of the plaster. It immediately closed together and was healed. “Now all is right,” he said to the spirit, “and we can part.”

The spirit thanked him for his release, and the scholar thanked the spirit for his present, and went back to his father. Thereupon the young man rubbed the bag on his damaged axe, and the axe turned to silver. He was then able to sell it to the goldsmith for four hundred thalers. He told his father, “You shall never know want; live as comfortably as you like.”

Thus father and son were freed from all worries. The scholar returned to his studies, and as the plaster he received from Mercurius could also heal all wounds, he became the most famous doctor in the whole world.

The End.

What we just heard is a fairy tale first published by the Brothers Grimm in the early 1800’s, originally in German. The title of this tale is The Spirit in the Bottle. And you can find it in any complete collection of Grimm’s Fairy Tales.

Now, what makes this story valuable to us in our expedition through Jung & Alchemy?

It’s the countless moments throughout the tale which are deeply symbolic but largely hidden from view. There’s even moments when the symbols are so tightly packed together that we can easily miss their meaning. But more importantly, this undercurrent of symbolism in The Spirit in the Bottle perfectly aligns with alchemy, and seems to directly reference it.

Jung noticed this too, and he dedicates a significant amount of time in his book, Alchemical Studies, to dissecting the hidden layers of this story.

Now why does any of this matter? Why should we spend any time trying to appreciate a centuries old fairy tale while trying to understand alchemy?

Well, from Jung’s perspective, a folk tale like this is a rich carrier of information, including cultural memories, archetypes and even elements from the collective unconscious. Jung states: “…we can treat fairytales as fantasy products, like dreams, conceiving them to be spontaneous statements of the unconscious about itself.”

At first glance, this is hard to fathom, the story just seems like any other story.

But here is where it gets interesting: by the 1700’s, alchemy is falling out of favor in public opinion, largely due to the developing science of chemistry combined with the dominant political powers of Christianity—which outlaws alchemy wherever it can. This folk tale is published by the Brothers Grimm around 1812, but it’s important to point out that the Grimms didn’t invent these fairy tales, they simply recorded them. It’s thanks to their documentation that we have such classics as Little Red Riding Hood, Snow White, and even Cinderella, along with hundreds of others. They transcribed stories that were being told from mother to child, father to son, and teacher to student. Stories which organically developed in communities where story telling served a purpose.

Such folk tales always come with important moral lessons but also they serve us as a kind of time capsule which can say something about that culture and period. Sometimes a story can convey a truth that is more profound than simple facts alone.

Reflected in this tale is the gradual shift of alchemy out of the public sphere, and back into the cultural unconscious, where it then largely remains until the 20th century. This is beautifully represented in the story’s symbolic elements, such as the dark forest the young man wanders through, and the fact that the bottle is buried deep in the earth, within the roots of a massive oak tree—all of these are overlapping symbols of the unconscious—the dark forest, the dirt of the earth, and the roots of a tree.

The young man in the story encounters Mercurius, who is shown to be a kind of spirit of alchemy, due to his ability to grant the young man the power to heal wounds and transmute metals.

But the telling element here is that the story treats Mercurius not like a God, but like a demon or a djinn—who can be tricked into giving away his secrets. It’s important to note that by this time in Europe, Christianity had asserted itself as the dominant religious and spiritual force in Europe, and even persecuted free thinkers as heretics. And so, Mercurius is locked against his will in a glass vessel, and placed in the dirt of the forest—or cultural unconscious—to be rediscovered by a future time.

On this matter, in Alchemical Studies, Jung states:

“It is worth noting that the German fairytale calls the spirit confined in the bottle by the name of the pagan god, Mercurius, who was considered identical with the German national god, Wotan. The mention of Mercurius stamps the fairytale as an alchemical folk legend, closely related on the one hand to the allegorical tales used in teaching alchemy, and on the other to the well-known group of folktales that cluster round the motif of the ‘spellbound spirit.’

Our fairytale thus interprets the evil spirit as a pagan god, forced under the influence of Christianity to descend into the dark underworld and be morally disqualified.”

What strikes me as especially poignant is that the young man in the story is not a peasant or woodcutter like his father, but instead, we are told he is a scholar. In the various traditions of alchemy, one thing that is always reiterated like a prerequisite to the work, is that one must read diligently and study frequently. A scholarly intellect is one of alchemy’s virtues.

For example, in the alchemical treatise, Atalanta Fugiens, written by Michael Maier, we find this passage, from discourse 42:

“Therefore the first intention must be to intimately contemplate Nature and to see how she proceeds in her operations, to this end, that the natural Subjects of Chemistry, without defect or superfluity may be attained to.

From whence let Nature be thy Guide and Companion of so great a journey, and follow her Footsteps. In the next place, let Reason be like a Staff which may keep the feet steady and Firm, that they may not slip nor Waver; for without reasoning, any person will be apt to fall into Error. Whence the Philosophers say, ‘Whatever you hear, reason upon it, whether it can be so or no.’

This book, Atalanta Fugiens, was first published in 1617, some two hundred years before Grimm’s book of fairy tales. It is written by a renowned author and alchemist, Michael Maier. And this is considered one of his masterpieces, not only for its insights into alchemy but also because it is one of the first works of multimedia in history.

It features 50 discourses on alchemy, and each discourse is paired with an original artwork, a poem, and a fugue written in music notation. In reading it, your mind is steeped in multiple symbolic layers—creating a rich world of symbolism that a scholar’s intellect can enter.

Discourse 42, which we just quoted, is paired with an artwork that depicts a maiden walking in the foreground, during nighttime, with a waning crescent moon in the sky. She is dressed in a flowing gown, carrying a bouquet of flowers in her right hand and fruits and vegetables in her left. Her feet leave footprints on the path, which are being closely followed further down the path by a bearded man.

The man has a cane in his right hand, an illuminated lantern in his left, and he is wearing a pair of glasses. The text above the emblem reads: “Nature, Reason, Experience, and Reading must be the Guide, Staff, Spectacles, and Lamp to him that is employed in Chemical Affairs.”

And this is the spirit with which Jung carried on his research of alchemy, with an insatiable scholarly intellect. This is also what we, my dear listener, are attempting to do in this series. We are following Jung’s footsteps, and where he paused his journey, we are picking up the lantern and continuing on.

Let’s turn our attention back to the story, there are still a few key symbolic elements we missed.

Remember in the beginning, when the young man returns home from his studies because his father’s money has run out.

The father says, “I can give thee no more, and in these hard times I cannot earn a farthing more than will suffice for our daily bread.”

The son responds, “Dear father, do not trouble thyself about it, if it is God’s will, it will turn to my advantage. I shall soon accustom myself to it.”

It’s curious that an element of divine will enters the story right from the outset, because in alchemy, the Great Work is thought to be guided by providence and revelation. And so, this establishes a narrative undertone, that what follows is a spiritual journey, whatever happens will be God’s will. The young man has now placed himself into the proper position of humility and reverence to receive the work.

Next we have the forest, which we already elaborated on, but notice something else which makes this story impossibly clever…After father and son work for a bit near the forest, they decide to rest and have their dinner. A meager helping of bread shared between them.

The father says, “We will rest, and have our dinner, and then we shall work as well again.”

The son took his bread in his hands, and said, “Rest thou, father, I am not tired; I will walk up and down a little in the forest, and look for bird’s nests.”

“Oh, thou fool,” said the father, “why shouldst thou want to run about there? Afterwards thou will be tired, and no longer able to raise thy arm; stay here, and sit down beside me.”

The son, however, went into the forest, ate his bread, was very merry and peered in among the green branches to see if he could discover a bird’s nest anywhere.

If you recall from our last episode, Codex 40, we explored animal symbolism in alchemy. Birds are creatures of the air, synonymous with spiritual matters, the soul, and all things celestial. This further supports the symbolism that the scholar is entering the forest / unconscious on a spiritual journey. And of course, eggs in a nest can indicate a new beginning, or birth.

The distant voice he hears calling from beneath the enormous oak tree is akin to the voice one hears within, that attempts to call your attention through intuition. The glass bottle he pulls out of the earth is clearly an alchemical vessel. And then something else entirely unexpected: do you recall what the young scholar first sees within the bottle?

The story reads: “He lifted it up and held it against the light, and then saw a creature shaped like a frog…springing up and down in it.”

In this context, the choice of a frog reminds me of a frog shown in certain alchemical manuscripts known as the Ripley Scrolls. These are hand painted scrolls that depict alchemical processes described by the alchemist, Sir George Ripley from the 1600’s. Each one is unique and painted by a different artist, including vivid imagery showing animals, dragons, and humans, along with text from the treatise. There are 23 Ripley Scrolls in the world, and on occasion they are brought out for museum display.

In 2017, one Ripley Scroll was sold through Christie’s auction house for the whopping sum of $728,000. Which makes me think there are more than a few eccentric millionaires out there that pursue alchemy in secret. But as we’ll learn later in the episode, this is the way it has always been—alchemy is no peasant’s art.

You can watch a great video on the Christies website that shows closeups of this Ripley Scroll. I’ve included a link to that in the episode description.

(Video about a Ripley Scroll up for auction by Christies auction house:

https://www.christies.com/features/The-fantastic-world-of-the-Ripley-Scroll-8760-3.aspx )

On the uppermost area of the scroll, we see an alchemist, positioned as a kind of creator God, looking down on the work taking place in the alchemical womb that is his glass vessel. The corked vessel itself is called a pelican, whose distinct shape is specific to the work of alchemy. But closest to him, inside the neck of the bottle, we see the culprit in question: a frog or a toad.

But what does it mean?

I wasn’t entirely sure. But I knew the answer must be somewhere. I started trying to track down any mentions of frogs or toads in the alchemical treatises. Do you recall, in the last episode, the toad was used in Michael Maier’s book, Atalanta Fugiens, Emblem 5, in which the toad is placed to a woman’s breast to suckle milk.

I stared at it…that only confused me further. I read the discourse twice…and that honestly didn’t help.

Then I realized, these Ripley Scrolls are all based off of a text written by the alchemist, Sir George Ripley. I tracked down some of his writings…and struck pure gold. In alchemical lore, Ripley is credited with having had a visionary experience, which revealed to him an alchemical secret—a magical elixir.

Ripley wrote this vision in the form of a poem, that all future alchemists would later study, the same way that they studied the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus. The poem is simply called The Vision of Sir George Ripley.

It follows:

When busie at my Book I was upon a certain Night,

This Vision here exprest appear’d unto my dimmed sight:

A Toad full Ruddy I saw, did drink the juice of Grapes so fast,

Till over-charged with the broth, his Bowels all to brast:

And after that, from poyson’d Bulk he cast his Venom fell,

For Grief and Pain whereof his Members all began to swell;

With drops of Poysoned sweat approaching thus his secret Den,

His Cave with blasts of fumous Air he all bewhited then:

And from the which in space a Golden Humour did ensue,

Whose falling drops from high did stain the soyl with ruddy hue.

And when his Corps the force of vital breath began to lack,

This dying Toad became forthwith like Coal for colour Black:

Thus drowned in his proper veins of poysoned flood;

For term of Eighty days and Four he rotting stood

By Tryal then this Venom to expel I did desire;

For which I did commit his Carkass to a gentle Fire:

Which done, a Wonder to the sight, but more to be rehearst;

The Toad with Colours rare through every side was pierc’d;

And White appear’d when all the sundry hews were past:

Which after being tincted Ruddy, for evermore did last.

Then of the Venom handled thus a Medicine I did make;

Which Venom kills, and saveth such as Venom chance to take:

Glory be to him the granter of such secret ways,

Dominion, and Honour both, with Worship, and with Praise.

Amen.

What a poem. Did you notice the mention of the three stages of alchemy by their color? First black, then white, then Ruddy—meaning a deep red. Also the use of fire as a means to purify and remove the venom from the toad.

The style reminds me of Emily Dickinson in parts. Especially the final verse: Then of the Venom handled thus a Medicine I did make; Which Venom kill, and saveth such as Venom chance to take…

In Emily’s masterpiece, My Life Had Stood A Loaded Gun, she writes:

Though I than He—may longer live

He longer must—than I—

For I have but the power to kill,

Without—the power to die—

To hear more about that, be sure to check out our episodes all about Emily, that’s episodes 18 and 19.

So what is Ripley talking about here? The toad and all… I haven’t read any analysis of this text, though I suspect many exist. In the spirit of charting a new path into the wilderness, I’ll give my interpretation.

I suspect Ripley is divulging a formula in the beginning stanza for a certain alchemical operation, a process which he then continues to describe. The toad, may indicate the metal mercury, as the metal is highly toxic and the poem refers to venom multiple times. Mercurius is also known to be the god that can traverse multiple worlds, as does the toad—the water and the land. And Mercury is also often associated with the dragon and the green lion. This again coincides with our folk tale, The Spirit in the Bottle, in which the scholar first meets Mercurius in the form of a frog.

But what is Ripley combining Mercury with?

In the third line of the first stanza we see this:

“A Toad full Ruddy I saw, did drink the juice of Grapes so fast”

This one set off alarm bells. The juice of grapes—wine—something to do with a wine based alcohol. In a modern alchemical treatise by the alchemist, Jean Dubuis, he mentions the usefulness of alcohol in alchemical operations, though in this case, he is speaking specifically of operations involving plants, a practice called Spagyrics. He states:

“In Spagyrics, the operation which consists of pouring alcohol on can be considered closest to the operation of fecundation.”

Fecundation is a word akin to fertilization. In another area of the text, he mentions that a wine based alcohol is most preferable for these operations.

This is all just conjecture of course, and I may be entirely off the mark, in fact—I probably am. A week from now I’ll realize it’s something else entirely. But this is the process one goes through in trying to unlock the secrets of any of these alchemical treatises. This is the inquiry it demanded from alchemists in the 1600’s. It makes you go in circles, comparing several different threads. Perhaps that’s why someone paid close to a million dollars for this one.

And we know that this was also the same effect alchemy had on Jung. Try as he might, there were some aspects of alchemy which seemed to always elude him, despite his scholarly rigor. His colleague, Marie-Louise von Franz once mentioned that in his attempt to understand alchemy, Jung created a lexicon, a table of all the symbols and terms which he would come across in the treatises.

He wrote down all the possible definitions and cross referenced them with every other text, trying to triangulate the one true definition for every symbol and phrase. In the end, von Franz says that Jung’s lexicon was a thousand lines long.

Despite all of this, Jung admits that some symbols cannot be limited to one definition, that there are aspects of alchemy that seem to morph and shift in definition depending on the individual alchemist. And so, when alchemist A talks about the stone, for example, he likely means something else entirely than alchemist B.

This is the very spirit of Mercurius. A god not tethered by physical limitation or celestial limitation—Hermes-Mercurius can travel throughout the heavens, the physical plane, and the underworld at will. He is a divine energy which the alchemists often refer to as a hermaphrodite, containing both masculine and feminine qualities.

Add to that the behavior of the physical substance itself, quicksilver, which is another paradox. It is the water that does not wet. I’ve seen this experiment demonstrated: take a container of mercury at room temperature, and pour water into it, the water and the mercury will not mix. Even if you take a spoon and try to mix them. But then, you submerge a paper towel into it, and the paper towel will absorb all of the water but none of the liquid mercury.

It boggles the mind.

Add to that, if you begin to heat it, mercury is extremely volatile, and will become vapor quickly, going—as The Emerald Tablet states—from the earth into the heavens.

If there is a god of alchemy, it is Hermes-Mercurius. Of all the deities in the treatises, it is Mercury who is most often mentioned, invoked, or praised.

In the first discourse, of Michael Maier’s Atalanta Fugiens, we find this passage:

“Nor is it indeed without reason that Mercury is called the Messenger or Interpreter & as it were the running intermediate Minister of the other Gods & has Wings fitted to his head & feet; for He is Windy & flies through the air as wind itself, which many Persons are really & experimentally convinced of, to their great damage.

But because he carries a Rod or Caduceus about which two serpents are twined across one the other, by which he can draw souls out of bodies & bring them back again & effect many such contrarities, He is a most Excellent figure or representation of the Philosophical Mercury…”

The final point to make on this fairy tale, The Spirit in the Bottle, concerns the place the scholar discovers Mercurius: deep in the earth, in the roots of a tree.

Jung points this out to us, stating: “The secret is hidden not in the top but in the roots of the tree…The roots extend into the inorganic realm, into the mineral kingdom.”

If part of what alchemists are practicing is an early form of psychology, as Jung claims, then we can say that the minerals, such as salt or sulfur, and the metals, such as lead, mercury, silver, gold, and so on…these are all found beneath the surface of the forest floor. Deep within the dirt. In fact, the deeper you dig, the more likely you are to find a mineral or a metal.

The alchemist’s work then is done primarily with material found in the symbolic unconscious of the earth. And the act of taking such material, such as lead, and attempting to purify it through repeated processes, to bring it to a state of perfection—into silver or gold… this is an exteriorization of psychoanalysis.

What happens in the alembic happens in the alchemist and vice versa. So as the alchemist is working with matter that represents unconscious content, he also compels such work to occur within himself. Bringing about visions, memories, and reflections which help him to work with the unconscious matter in his own psyche.

INTERMISSION:

And now it’s time for a brief intermission…

If you’re enjoying this Jung & Alchemy series, please share it with someone. It’s the best way to help this little sunflower grow.

I’m proud to say that there is no other podcast out there that does what we do. And we are coming up on a very special milestone: our five year anniversary!

Yes, Creative Codex is five years old! What a ride it’s been, and there is so much I want to say about it, but I am saving that for a special anniversary episode I’m working on, which we will release right after the Jung & Alchemy series is complete. The five year anniversary episode will be a Listener QnA.

Here is where you come in. If you have a good question about any of the creative geniuses we’ve covered on the show, or about creativity, or about the show itself, I want to hear it. There’s a few ways you can send me your questions. If you’re listening on Spotify, just open the episode description, and there you can type your question to me.

You can also send me a message on Instagram, that’s @mjdorian. Or, if you support the show on Patreon, you can write me a message there.

At this point of the episode, in most podcasts, you’d hear an ad for fentanyl flavored ice cream, or horse viagra, or Presidential Tarot, the new novelty Tarot deck featuring all your favorite and least favorite American presidents. Can you guess who The Fool card is?

But not on Creative Codex. Instead I’d like to tell you about a crazy new project I’m working on as a thank you for my Patreon supporters. I call it Red Book Reading.

During my research for the most recent episode of the Jung & Alchemy series, I stumbled on a passage in The Red Book which I had never heard anyone discuss or interpret, and which stunned me with its profound relevance to the work we were doing: tracing Jung’s discovery of alchemy. (I recite this passage at the end of Codex 40.)

Although I read and studied the entire Red Book four years ago, this passage meant little to me at that time. The startling effect implied: as the light of my understanding grew, the book revealed new depths.

What other gems are still hiding in The Red Book?

This is the impetus of the current project: to give the entire Red Book the Creative Codex treatment––complete with original music and sound design.

This is an enormous undertaking. The total runtime of the final version will be between 15 to 20 hours. I will be releasing it one chapter at a time, once a month. This first offering is free for patrons and non-patrons. All future chapters will only be available to the $5-and-up tiers, as a show of my gratitude for your continued support.

The journey begins.

Here is a sample from the first chapter of my Red Book Reading series:

[play Chapter 1 Part 1 sample]

That was a sample of my new Red Book Reading series. If you’d like to support the show and gain access to each new chapter, which I’ll be releasing once per month, simply head over to patreon.com/mjdorian, that’s patreon.com/mjdorian.

And I thank you in advance for your support.

Without further ado, back to Carl Jung & Alchemy • Part 3: Magnum Opus.

Chapter 5: Magnum Opus

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about how alchemy was outlawed and persecuted throughout the centuries—but this isn’t the full truth.

There was a time period in Europe when alchemy was celebrated as a royal art. As a tradition that attracted philosophers, intellectuals, and one which was meant to be practiced in the courts of kings and nobles.

It was during this time period, from 1500 to 1700, that so many of the most famous artworks and treatises arose, with the funding and support of wealthy backers.

As we hinted at before, alchemy was never a peasant’s art—it demands too much of its practitioners. First you must dedicate a laboratory space for the work, and prepare it to withstand unpredictable fires and high temperatures, a simple wooden hut won’t do. Then you must acquire a few dozen specialized glass vessels, of the highest quality—to also withstand high temperatures, and don’t forget all of your supplies—the working materials themselves: special plants, minerals, and rare metals.

With the understanding that some of your materials will very likely perish in failed experiments, due to a lack of experience or personal failings—perhaps you were not in the right state of being for the desired effect to manifest.

And with all of this in mind, finally comes your most important asset: time. The time to study and understand dozens of alchemical treatises, half of which are in foreign languages which you must translate.

All of that to say… you must have an expendable income and a degree of leisure time. Perhaps you don’t have to be rich to pursue it, but it would certainly help to at least be in the middle class.

Now let’s take a journey back in time to a place and a period when alchemy was at its height. The late 1500’s in the golden city of Prague.

[time travel transition sound]

[sound of 1500’s city, horse carriage, distant church bells, people walking, talking]

Right now, we’re standing on Charles Bridge, in the golden city of Prague, the capital of historic Bohemia. The year…is 1580. This enormous medieval stone bridge under our feet stretches across the Vltava river. It is supported by 16 impressive arches. Charles Bridge is the only connecting point between Prague Castle and the Old Town district.

If you look down the length of the bridge, you can see three gothic defense towers, one on each eastern and western end and one near its center. Guards are always stationed here, both as a lookout and a local arm of the law.

And there, just behind you, on the western end, you can see the towering spire of St. Vitus cathedral as it pierces the sky.

This is the King’s cathedral, it stands proudly near the largest castle complex in the world: Prague Castle, the home of the King of Bohemia, Rudolf the 2nd. He’s a noble and tolerant king, and although he carries the title of Holy Roman Emperor by decree of the Catholic church, his personal interests include astrology and even alchemy.

But we are not crossing the bridge to visit him, instead, our destination is in the opposite direction, toward the Old Town district.

Let’s make our way there.

I love these intricate cobblestones, it really wouldn’t be a Renaissance city without them. Ok, the Old Town Square is this way.

[stones change to dirt or hard concrete sound, then sound of market square]

There’s a market here everyday, with merchants selling fresh vegetables, herbs, live chickens, fabrics, fish, books, candles, spices, and foreign trinkets from traveling merchants. [sniff] Someone is burning sage.

Prague is an affluent city in central Europe and it’s a key trade route. If you need anything at all, your best bet is the market square.

A statue of Rudolf II stands right at the center, overlooking the activity of the square. Unlike most rulers, the common folk here love their King. But even more than the common folk, the occultists love the King. He is known throughout Europe as one of the greatest patrons of alchemy. If you’re an alchemist in the late 1500’s, you will at some point consider a voyage to Prague in the hopes of earning favor from Rudolf the IInd, or a stipend for your work, perhaps support for a new treatise.

By this point, he has supported the who’s who of alchemy, from the likes of the notorious magician, John Dee, to the Polish alchemist Michael Sendivogius, who is known as the first person to discover and document the existence of oxygen. In addition to these luminaries, Rudolf the IInd also supports Michael Maier, the author of our recent favorite treatise: Atalanta Fugiens.

We’re going to turn here now, at Hastalska Street. These charming arched alleyways appear throughout the entire old district. And here, those expensive stones are replaced by hard earth.

We’re now entering the Jewish district of the city. King Rudolf the IInd is celebrated for his tolerance of non-Christian citizens, and specifically the Jewish population of Prague. This is a fortuitous arrangement for alchemists of the region, as the study of alchemy goes hand-in-hand with the study of Kabbalah, a spiritual philosophy that is borne out of the Jewish mystic tradition.

What we’re looking for is a certain house. The locals know it as the House of Rabbi Loew, a Jewish mystic, mathematician and scholar. But the building itself hides an even more intriguing secret…beneath it is an alchemical laboratory.

People sometimes complain of sudden bursts of flame from the metal grates in front of the house. There’s even a local legend of a golem that lurks in the shadowy lanes of the town at night. Is it some monstrosity summoned through an act of black magick? No one knows.

Ah, there, that building! That’s it. Do you see the wooden sign hanging from the front wall? It’s etched with the alchemical symbol of Mercury.

We’re going to use this side entrance, that should take us down.

You wouldn’t know it, but there are stone passageways under these streets. Like the one we’re entering now. These are some of the oldest structures in Prague, records show this building, the House of Rabbi Loew, existed as far back as 900 AD, making it the second oldest building in Prague.

Remarkably, these stone tunnels stretch under the entire city, connecting the three most important places: Prague Castle, Old Town Hall, and the Barracks.

But why? Are they here as a possible escape route in case of war? Or are they a way for the King to travel under the city without alerting people to his whereabouts…or his occult interests?

This passage could certainly do with a little more light, I can hardly see anything down here. Ah, you see that reddish glow coming from that doorway to the left, that’s where we’re headed. Watch your step.

Can you make out the carving on the door? It’s a set of alchemical symbols.

We’re here. Let’s have a look inside.

Wowwww… Look at all this stuff. Alembics, retorts, pelicans, flasks, there must be over a hundred glass vessels in here, some of them even have colorful substances inside of them. All along the walls, there are candles in alcoves lighting up the space, their flickering makes the stillness of the room come alive.

It’s really hot down here, like someone left the oven on. Well that explains it, there, in the corner is an enormous furnace. And someone is hunched over in front of it…it must be the alchemist, focusing on an operation—he is blowing air into the fire of the furnace with a bellows. Let’s look around, we’ll try not to disturb him.

Here, this must be the alchemist’s work desk. Yes, the quill, the ink pot, and all of these countless scrolls and parchment pages—these must be alchemical treatises.

There is one very long page that looks like some kind of list or table. It must be a lexicon of all the symbols and phrases this alchemist has studied in his readings. And next to it, right in the middle of the desk is some massive tome. It’s wrapped in brown leather with these latin words carved into its spine: Magnum Opus…The Great Work. This is a term which first originates in alchemy. But what does it mean?

Inside are writings…in German and Latin. It’s like a journal of reflections and musings…documenting results of the work, including drawings, and even paintings, executed right on the thick parchment.

What is this?

And what is the goal of the Magnum Opus?

Surely it can’t simply be to create small handfuls of silver or gold. If that’s all it was, why would the wealthiest nobles and royalty alike be interested in it? The people who are least in need of pocket change.

To answer this, we must reach deeper into the philosophical DNA of alchemy. Although alchemy existed parallel to Christianity for centuries, it remained distinctly separate from it, because at its heart it contains a dramatically different perspective on reality.

Christianity tells us we are born into sin, and that the material world around us is filled with temptation and demons vying for our attention. Material reality requires redemption because it is corrupted by original sin. We are guilty and we should feel guilty. Our only hope for redemption is through the church, through its various officials and religious authorities.

In contrast, alchemy puts forward a very different set of circumstances. It proclaims: within each piece of matter is a spark of the divine. A spark of light which can only be released through the intervention of man. A task only accomplished through the separation, purification, and re-unification of the matter in the alembic.

Alchemy is a redemptive act, of both matter and the self, but it is one performed entirely through the alchemist’s will and individuality. It is a solitary work which requires no confirmation by any religious authority.

In this regard, alchemy is much closer, philosophically, to Gnosticism and Hermeticism.

This is why Jung draws his line from Gnosticism to alchemy and then to analytical psychology—because he sees the essential ingredient which connects all three: the potential for transformation and growth through turning the self inward.

Every individual is an ouroboros. A venomous snake which bites its own tail—conveying poison to the wound while also harboring the secret antidote.

The Magnum Opus which lies on the alchemist’s work desk, filled with writing and artwork—that is the alchemist’s Red Book. In this case, an attempt to perfect matter through the divine sparks locked within it, and in the process, to perfect the self.

The similarity between what the alchemists were doing and what Jung does in his Red Book is no coincidence. Both were tapping into the same rich material of the unconscious.

And we can confirm this through the stunning similarity in the texts written by alchemists, which resemble the same dialogues which Jung records in his Red Book. Bear in mind, that Jung works on the Red Book for years before stumbling on any of these types of alchemical writings.

For example, here is a passage by the alchemist, Gerhard Dorn, from the mid-1500’s. In it, Dorn writes a dialogue between his soul, his spirit, and his body. Side note: this text was translated by Marie Louise von Franz, and appears in her book titled: Alchemical Active Imagination. According to her interpretation, when Dorn refers to the term Philosophical Love, he is referring to alchemy.

Dorn writes:

Spiritus says: “Well then, my Soul and my Body, get up, and follow your guide.”

Animus responds: “He wants now to go to this high place on this mountain opposite us. From its peak I will show you a double path, the bifurcation of a path about which Pythagoras already had a dim idea, but we whose eyes have been opened and to whom the sun of piety and justice shows the way will not fail to find the path of truth. Now look with your eyes to the right side, so that you cannot see the vanities and superficialities on the left path, but look rather over to wisdom. Do you see the beautiful castle over there?”

Anima and Body respond: “Yes.”

Spiritus continues: “In it dwells Philosophical Love, from whom flows the source of living water. He who has had a sip of it will never thirst again in this dull world. From that agreeable place we must then continue directly to an even more beautiful place, which is the dwelling place of Wisdom; and there too you will find a spring of the waters which will give more blessings, for even if enemies drink of it they are forced to make peace.

There are people who even try to strive higher, but they do not often succeed. There is to the north a place which mortal people may not enter if they have not previously entered a divine, immortal state, but before they really reenter it, they will have to die and throw away their earthly lives.

Whoever has reached that castle has no reason to fear death anymore. Beyond these three places there is even a fourth place, which is beyond anything people can know. The first place you could call a crystal castle, but the fourth one is invisible: you will not even be able to see it before you have reached the third. It is the golden place of eternal bliss.

Now look to the left side, there you see the world full of its desires and riches and everything which pleases the mortal eye. But look at the end of that path: there is a dark valley full of mist which expands to the end of the horizon—that is Hell.”

Anima and Body respond: “Yes, we see it.”

Spiritus: “Now we are going on this broad path, the path of Hell, and there every comfort is turned into torture without end. Do you hear how the people howl and are in despair?”

Anima and Body: “Yes, we hear, but will the people not return from there?”

Spiritus: “They cannot see the end of this, and that is why they just go on, and they have generally already passed the place of repentance and therefore cannot return anymore.”

Anima and Body: “There are also other paths in which one can get into danger.”

Spiritus: “Yes, there are two side paths which also bifurcate away from us and of which I will tell you later. Now we are going on to that place ahead, namely on those two paths, the Heaven and Hell paths, after which there are two more paths, and those are the paths of illness and poverty, which are between Heaven and Hell.

They do not lead to Heaven or Hell; many people take them and then after a while illness and poverty teach them to return to the right path or may even force them to go on the path to Hell; so they are in an in-between stage of ever trying and being unhappy, and one just does not know which way they will end.

The broad path to the left is the way of error, and the other two paths are the ways of illness and poverty, and the path on which we are now standing, if we move over to the other side, is the path of the truth, and on the entrances to this path the angel of the Lord stands who is called the tractus of the Divine.

Here, even at the first path, this tractus attracts them all, but there are people who resist it and do not go that way, as they want to give in to their momentary impulses and desires. Those fall into physical illness, and there are only a few who through physical illness can see their error and then return to the path of truth.”

The bizarre thing about this dialogue, which was written in the 1500’s, is that if we were to come across this exact passage in Jung’s Red Book it would not feel out of place. Strange, right?

Whatever the alchemist, Gerhard Dorn, is tapping into here, in exploring these philosophical, spiritual, and psychological concepts feels parallel to what Jung is doing, some 400 years later. How do we explain this?

Jung has a name for what this state of mind is, he calls it: active imagination. It’s a term he coined which refers to this act of turning a fantasy in on itself, and observing the scenes as they unfold with minimal influence. In analytical psychology, this method has a very real therapeutic application.

And we now know that Jung was using this method in his therapy sessions, after years of working with it himself. There is a written account from one of his patients in 1926 which confirms this. It is included in the introduction to the published Red Book, in the section written by Sonu Shamdasani. A woman named Christiana Morgan recalls Jung telling her this:

“I should advise you to put it all down as beautifully as you can—in some beautifully bound book. It will seem as if you were making the visions banal—but then you need to do that—then you are freed from the power of them.

If you do that with these eyes for instance they will cease to draw you. You should never try to make the visions come again. Think of it in your imagination and try to paint it. Then when these things are in some precious book you can go to the book & turn over the pages & for you it will be your church—your cathedral—the silent places of your spirit where you will find renewal.

If anyone tells you that it is morbid or neurotic and you listen to them—then you will lose your soul—for in that book is your soul.”

Jung wasn’t only guiding his patients through the use of the method of active imagination, he was encouraging his patients to create their own Red Books.

The author, Jeffrey Raffe, who was once a student of Marie Louise von Franz, and who also wrote the book, Alchemical Imagination, states this:

“Active imagination is Jung’s technique for the transmutation of the soul.”

So where can we find a description of this method?

I stumbled on several passages about it in Jung’s book, Mysterium Coniunctionis. In this text, which is a 600 page analysis of Alchemy and its psychological significance, Jung refers to active imagination as a psychotherapeutic method.

Mysterium Coniunctionis is a latin term, meaning ‘the mysterious union,’ and it originates in alchemical treatises. This book is the last great masterwork of Jung, and so it contains the culmination of a lifetime of reflection on the subjects of both alchemy and psychology.

In describing active imagination, Jung writes:

“This is a method which is used spontaneously by nature herself or can be taught to the patient by the analyst. As a rule it occurs when the analysis has constellated the opposites so powerfully that a union or synthesis of the personality becomes an imperative necessity.

Such a situation is bound to arise when the analysis of the psychic contents, of the patient’s attitude and particularly of his dreams, has brought the compensatory or complementary images from the unconscious so insistently before his mind that the conflict between the conscious and unconscious personality becomes open and critical.

[…] In nature the resolution of opposites is always an energetic process: she acts symbolically in the truest sense of the word, doing something that expresses both sides, just as a waterfall visibly mediates between above and below. The waterfall itself is then the incommensurable third. In an open and unresolved conflict dreams and fantasies occur which, like the waterfall, illustrate the tension and nature of the opposites, and thus prepare the synthesis.

This process can, as I have said, take place spontaneously or be artificially induced. In the latter case you choose a dream, or some other fantasy-image, and concentrate on it by simply catching hold of it and looking at it.

You can also use a bad mood as a starting-point, and then try to find out what sort of fantasy-image it will produce, or what image expresses this mood. You then fix this image in the mind by concentrating your attention.

Usually it will alter, as the mere fact of contemplating it animates it. The alterations must be carefully noted down all the time, for they reflect the psychic processes in the unconscious background, which appear in the form of images consisting of conscious memory material.

In this way conscious and unconscious are united, just as a waterfall connects above and below. A chain of fantasy ideas develops and gradually takes on a dramatic character: the passive process becomes an action.

At first it consists of projected figures, and these images are observed like scenes in the theatre. In other words, you dream with open eyes. As a rule there is a marked tendency simply to enjoy this interior entertainment and to leave it at that. Then, of course, there is no real progress but only endless variations on the same theme, which is not the point of the exercise at all. What is enacted on the stage still remains a background process; it does not move the observer in any way, and the less it moves him the smaller will be the cathartic effect of this private theatre.

The piece that is being played does not want merely to be watched impartially, it wants to compel his participation. If the observer understands that his own drama is being performed on this inner stage, he cannot remain indifferent to the plot and its dénouement. He will notice, as the actors appear one by one and the plot thickens, that they all have some purposeful relationship to his conscious situation, that he is being addressed by the unconscious, and that it causes these fantasy-images to appear before him.

He therefore feels compelled, or is encouraged by his analyst, to take part in the play and, instead of just sitting in a theatre, really have it out with his alter ego.

For nothing in us ever remains quite uncontradicted, and consciousness can take up no position which will not call up, somewhere in the dark corners of the psyche, a negation or a compensatory effect, approval or resentment.

This process of coming to terms with the Other in us is well worth while, because in this way we get to know aspects of our nature which we would not allow anybody else to show us and which we ourselves would never have admitted.

It is very important to fix this whole procedure in writing at the time of its occurrence, for you then have ocular evidence that will effectively counteract the ever-ready tendency to self-deception. A running commentary is absolutely necessary in dealing with the shadow, because otherwise its actuality cannot be fixed. Only in this painful way is it possible to gain a positive insight into the complex nature of one’s own personality.”

There is a tremendous potential for transformation and growth through turning the self inward.

Every individual is an ouroboros. A venomous snake which bites its own tail—conveying poison to the wound while also harboring the secret antidote.

On the next Creative Codex…

On the final episode of this series, we face a strange conflict between what Dr. Jung says about alchemy and what alchemists say about alchemy. Who do we believe? Is the clear spiritual component to the alchemical work tangible and real or is it all just psychology shrouded in chemical jargon?

We will also explore the influence of archetypes and the collective unconscious on the great work, the profound meaning of the three principles of salt, mercury, and sulfur, and finally: by the next episode, I will be practicing alchemy. It’s time to put these ideas to the fire.

All this on the final episode of this series: Part IV of Carl Jung & Alchemy. I’ll see you then.

PATREON

Become a patron of the show, and gain access to all the exclusive Creativity Tip episodes, as well as episode exclusives. Just click the button or head over to: https://www.patreon.com/mjdorian

Wanna buy me a coffee?

This show runs on Arabica beans. You can buy me my next cup or drop me a tip on the Creative Codex Venmo Page: https://venmo.com/code?user_id=3235189073379328069&created=1629912019.203193&printed=1