EPISODE TRANSCRIPTS

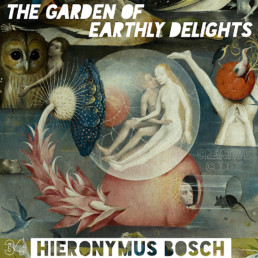

34: Hieronymus Bosch • Secrets of The Garden of Earthly Delights (Part I)

Imagine creating a work of art that is so out of the ordinary, so bizarre by the norms of culture, that people call you mad–verifiably unwell. And not just the people of your time and country, but even more-so, the people of neighboring countries, and even future times.

Saying things like “Well, she was clearly disturbed, just look at this thing.” And things like “There’s no way someone can create that without either being high… or insane.”

These are the things that people have been saying about the artist: Hieronymus Bosch…for centuries. Every new generation levels a new accusation at him–and perhaps rightfully so. Bosch is the creator of one of the strangest and most puzzling paintings in art history: The Garden of Earthly Delights, which he completed sometime between 1495 and 1505. It’s a painting with a reputation for equally confusing and titillating viewers.

Art critics one hundred years after Bosch’s death felt confident in saying that he was a disturbed man painting the outlines of his own madness. And people four centuries later, in the 1960’s, were saying he clearly must have taken psychedelic mushrooms to create such imagery.

I suppose that’s an improvement from simply calling him insane–but still. Have we considered the most likely alternative: Bosch was an outlier genius. One of these rare individuals who comes along, and sees the world so differently than the rest of us, that it forces us to reconsider…’wait, maybe we’re the crazy ones.’

And that’s what this episode is about… Hieronymus Bosch and The Secrets of The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Side note: if you’d like to see a visual companion to this episode, which will show you the artworks we discuss in real time, just listen to this episode on Spotify. I’ve created a video companion for it that will automagically play along in your Spotify app or desktop browser when you click the play button on this episode.

If you would prefer to explore the Garden of Earthly Delights at your own pace, there is a high resolution version of it available online which you can easily access.

The links for both options are in the episode description.

This is Creative Codex, I am your host, MJDorian.

Without further ado, strap yourselves in… It’s time to get weird.

[music]

Chapter One: An Owl In The Wilderness

In the year 1503, Hieronymus Bosch is in the Netherlands, working on his masterpiece: The Garden of Earthly Delights. At this exact moment, in Italy, a thousand kilometers away, is Leonardo da Vinci, working on a painting called Virgin of the Rocks.

While Leonardo is painting the Virgin Mary, Bosch is painting a nude man being seduced by a pig dressed as a nun. Yes.

Similarly, at this exact moment, elsewhere in Florence, Michelangelo is sculpting his statue of David. While back in the Netherlands, Bosch is painting a man shoving a bouquet of flowers into another man’s butt…also an enormous bird feeding red berries to a crowd of people… and a man being skewered on the strings of a harp…

What in the hell is going on here?

How can Bosch’s artwork exist during the same timeline as Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s? It looks so thoroughly modern. As if it was created in the 20th century, not the 16th. How do we reconcile that?

[music]

In looking at his most famous work: The Garden of Earthly Delights. We are faced with this challenging question: why did Bosch paint these images? And what did the people of his time have to say about them? But most importantly: what is Bosch trying to say?

The Garden of Earthly Delights is a visual metaphor. Something which, to our eyes today, is a very modern invention. Artists during his time period of the 15th and 16th centuries, just weren’t thinking of art in this way. These aren’t the doodlings of a madman. Far from it. This is the first time that we see an artist take something psychological and represent it through a visual metaphor on the grandest scale.

But to truly understand this masterpiece, we need to rewind a little bit.

And first understand who Hieronymus Bosch really was. This will give us the keys to unlock the secrets of The Garden.

[music]

It will surprise many people to know, that Bosch wasn’t some tortured artist, shunned by the public for his strange works, off painting his inspirations on the edge of town.

No… it’s the complete opposite. He lived a very comfortable life and he was well respected in his time.

The man we know as Hieronymus Bosch was born Hieronymus van Aken, in the city of ’s-Hertogenbosch, in the Netherlands. ’s-Hertogenbosch, in Dutch, translates as the Duke’s Wood.

It’s known to locals simply as Den Bosch. And that’s what we’ll call it in this episode. Hieronymus was born around 1450. An exact date of birth isn’t clear, because we only have a handful of existing records from Bosch’s life. But scholars agree that it was likely around 1450.

He was born to the Aken family name, hence Hieronymus van Aken would mean ‘Hieronymus of the Aken clan.’ His father was Anthonius van Aken and his mother was Aleid van der Mynnen. He had four siblings, an elder sister, a younger sister, and two elder brothers.

Now all of that seems pretty normal for a Dutch family in the mid-1400’s… But this surprised me: Hieronymus wasn’t the first painter of his family. Far from it.

His father, Anthonius, was also a painter. And Anthonius’ father, Jan Thomassen was also a painter… and his father before him, Thomas van Aken was also a painter. And Thomas van Aken’s father before him? Was a car mechanic…Just kidding, we don’t know. But I wouldn’t be surprised if art was the family business well into the medieval period.

That’s four generations of the Aken family that we know of who practiced fine art painting as their profession. That’s…incredible. And rare. According to scholars there are no other examples of such a fixed arts profession family tradition in the Netherlands at that time.

It means that Hieronymus was raised around art, he knew the in’s and out’s of its business, he knew who to speak to in town to acquire paints, he knew what brushes to use, knew how to hold a palette, all through being around art from his earliest childhood. Hieronymus held a brush before he could walk.

And he had four generations of knowledge imparted to him through his father’s, grandfather’s, and great-grandfather’s trial and error, specifically in painting.

Art was the family business. And in the 1400’s, the business was going well. The Van Aken workshop would receive commissions largely from cathedrals and church officials for religious work, but occasionally from wealthy patrons as well. If you lived in Den Bosch, and you needed a fancy centerpiece painting of your family’s coat of arms, well, you would head over to the Van Aken workshop and write up a commission. Bosch’s family would have been considered middle to upper middle class during this time.

Unlike many of the creative geniuses we cover on Creative Codex, we have no surviving letters, journals, or notebooks from Bosch or any members of his family. Which is a real shame. It would be priceless to be able to read some of Bosch’s thoughts on his paintings or his choices with certain symbolism. Like why did he paint a hooded duck creature reading a book in the bottom of the Garden of Eden panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights? What was he thinking there?

But historians have located roughly 50 legal documents, such as the sale of certain properties or commissions for certain works, which mention him or his relatives in various capacities, and that helps us piece together a story about his life.

For example, we don’t have a marriage document related to him, but we know he married named Aleid van de Meervenne sometime before July 1481, because after this date we see the two of them appearing on legal documents together, in their city of Den Bosch.

And likewise, we can assume that Bosch never attended a university, like the one in Cologne or Louvain because no documents record his attendance there, and he would have earned a title when graduating that later legal documents would refer to him with.

We do know that his marriage to Aleid, was a fortuitous one. She was from an upper middle class family, was likely a little older than Bosch, and had inherited several properties through her family.

The book, Hieronymus Bosch: Visions and Nightmares, the author, by Nils Buttner, gives us more details:

[music]

“By 1483, Bosch and his wife had moved into the house on the marketplace that had been rented out earlier, situated only a stone’s throw from Bosch’s family home. The house, called In den Salvatoer (At the Sign of Our Savior), had a frontage of 19 feet wide–with a stepped gable. Its four stories had a total surface area of 465 square meters.

An additional rear building also provided living and working areas, giving the family 650 square meters of space in total. A painting from around 1530, which is a view of Lakenmarket (the Cloth Market) shows Bosch’s impressive property, the seventh house from the right.

In 1553, by which time it had been occupied by other people for a good while, it had five fireplaces, a baking oven, a brewery and even a bath that could be heated. Although these conveniences might have been installed at a later date, the house nevertheless provided enough room for a workshop and a household befitting their social standing.

They would also have had a number of staff, such as the employees in Bosch’s workshop–his assistants–who according to a document from 1503 received six stuivers for producing three small coats of arms. Five stuivers was a quarter of a guilder and was about the daily rate for a master craftsman.

The family’s domestic work would also have been assisted; the records speak of the ‘servants in the kitchen’ and the ‘maids’ who were paid extra for festive banquets.”

[end music]

Now, why does any of this matter?

Well, it means that Bosch lived comfortably. It’s stated that at one point in his life he made enough money from his workshop and the rental of his wife’s properties that he did not need to rely on commissions for his livelihood. This afforded him the luxury of doing paintings in his own style. He could bend the rules and expectations, he could experiment a little bit. It afforded him the luxury of being weird.

At the end of the day, if someone didn’t like it, it wasn’t life or death. His residual income could still put food on the table.

Which brings us to his artist name… Why did he change it to Hieronymus Bosch rather than keep the family name of Hieronymus van Aken?

Certainly, coming from a noteworthy artist family had its benefits, so why change it?

The word itself, Bosch, means forest or wilderness in Dutch. It is contained in the name of Bosch’s city: ’s-Hertogenbosch. Or Den Bosch as the locals call it.

It might be that Bosch was thinking bigger. We know that in the latter half of his life, once he was in his fifties, his artwork begins to get the attention of royalty and even Kings in neighboring countries.

I suspect this is the kind of work he wanted. It afforded him the greatest prestige combined with the greatest artistic freedom. Creating a painting for a King who is well versed in the arts was much different than creating a painting for a cathedral. In which the rules of iconography and a rigid Catholic aesthetic come into play. Although we have every reason to believe that Bosch was a devout Catholic, and according to the consistent subject matter in his paintings, he was highly critical of the secular world.

In a sense, works like The Garden of Earthly Delights and other triptychs, like Haywain, depict to us Bosch’s personal view of material reality… that it is an illusion filled with pleasurable distractions which lead one to a hellish damnation. We will explore this more in the next chapter.

Concerning Bosch’s name change…

There is one document, from a prestigious Catholic fraternity which Bosch belonged to called the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady. Bosch is mentioned in their documents several times, and he was frequently commissioned by them as the resident artist–even creating several altarpieces for their cathedral.

In this one document, dating 1509, when Bosch would have been 69 years old, it is written:

“Hieronymus van Aken, painter, who signs himself Hieronymus Bosch.”

This tells us that by 1500, his alias was commonly known in the city, but legally, he retained his Van Aken name.

And so, I suspect for art, Bosch preferred the association to his city name rather than his family name. Bosch…The Wilderness…The Forest. It also had a more mysterious ring to it.

But one other important point to make…When you see something like The Garden of Earthly Delights, or one of Bosch’s other triptychs, like the Haywain… You can see he is pushing the envelope. Especially for his time period. And we can assume this is the type of work that excites him. That he finds most meaning in.

During the early 1500’s… Hieronymus Bosch was modern art. With all the sensationalism and controversy that goes along with that label.

The Bosch scholar, Stefan Fischer, writes this about him in the book, Hieronymus Bosch, The Complete Works:

[cue music]

“In an era described as Late Gothic by some and as Early Renaissance by others, in which art strove increasingly towards harmony and brilliance, illusionism and monumentality, the Netherlandish artist Hieronymus Bosch followed a very different path.

With his innovative pictures, often populated by grotesque figures, of a religious nature, the artist from ’s-Hertogenbosch properly falls neither into the Flemish panel-painting of the 15th century nor into the Renaissance style that spread north of the Alps in the course of the 16th century.

Albrecht Durer held the emphatically Renaissance view that an artist ‘should take care that he does not make something impossible, does not distort Nature, unless it be his task to make a picture of a dream. In such a picture he may mix all things together.’

In Durer’s book, in other words, Bosch–who was not concerned with the idealizing portrayal of nature–fell into the category of a painter of dreams. And this was exactly how Bosch would be seen for centuries right up to the present: as a fantastical visionary, a visual chronicler of dreams and nightmares and the painter par excellence of Hell and its demon–subjects frequently connoted in negative ways as ‘unnatural’…”

[end music]

So, there is a very real functional reason why Bosch would have chosen to be…Bosch. He knew where his artistic interests were leading. And changing his name protected his family name and their family business from being possibly tarnished through association with his artwork.

Legally, he was still Hieronymus van Aken… but artistically, he was his own creation: Hieronymus Bosch.

[music transition]

We’re going to take a brief intermission just to stretch our legs before we take a deep dive into The Garden of Earthly Delights.

If you’re enjoying this episode, please share it with someone. It’s really the only way that this little independent show grows. We don’t have the advertising budgets of these million dollar podcasts, but I know we have the best damn audience around. And if each person listening shared this show with even one other person… that would be a huge help. It’s really that simple.

And I thank you in advance for that.

If you’d like to buy me a coffee or drop some money in my fancy books fund, you can do so on Venmo. Just search @creativecodex on Venmo, and you will see us under Businesses.

I purchased four books about Hieronymus Bosch just for this episode, and I do equally intensive research for all the episodes of the show. If you’re looking to get a book about Bosch, I highly highly recommend the book titled: Hieronymus Bosch The Complete Works by Stefan Fischer. Published by the art publisher Taschen. T-a-s-c-h-e-n. It’s the perfect balance of beautifully printed prints of Bosch’s paintings and scholarly explanations of the works.

If you’d like to become a supporter of the show through Patreon, and gain access to exclusive episodes, such as my Kurt Cobain series, just head over to patreon.com/mjdorian

That’s… patreon.com/mjdorian

The link for that is also in the episode description.

One final note as we resume the episode… I feel it’s important to clarify: most of the core interpretations of the Garden of Earthly Delights painting I have acquired from research and reading scholarly sources. But many of the more unique interpretations of the symbolism are my own. From simply staring at the damn thing for hours. In these instances, of personal insights, I will try to mention that I haven’t read this or that in any of the books.

And now, back to the episode…

Chapter 2: Secrets of The Garden

The oldest description of The Garden of Earthly Delights comes from an unlikely source. Not from the missing journals of Bosch or from his correspondences. But rather from the travel journal of a man named Antonio de Beatis. Beatis was an assistant to a wealthy Italian Cardinal named Luigi d’Aragona.

Cardinal d’Aragona was a bastard son of a Marquis from Southern Italy, who himself was a bastard son of Ferdinand the 1st, King of Naples. Being wealthy and coming from such a distinguished family, the Cardinal thought it appropriate to take a pleasure trip through Europe to introduce himself to all the Kings of the lands, from Italy, through Germany, and to the Netherlands.

The Cardinal and his assistant, Antonio de Beatis, covered a distance of 39 kilometers a day, in decorated carriages drawn by up to 35 horses.

The journal of Beatis traces their voyage over the course of a year, from 1517 to 1518. It includes famous entries such as the one in which Beatis describes meeting Leonardo da Vinci in Amboise, France. And as we mentioned in the Leonardo’s Notebooks series, it is Beatis who writes down one of the only descriptions of Leonardo’s notebooks which we have from the time period, in which he mentions the countless pages of anatomical studies and other wonders.

Beatis also notes that he and Monsignor Cardinal met with King Francis, writing:

“King Francis was cheerful and most engaging, though he has a large nose, and in the opinion of many, including Monsignor Cardinal, his legs are too thin for so big a body.”

In their travels, Beatis, documenting things for the Cardinal, makes note of many details that give Renaissance historians precious information about the time period.

Such as that the women in Germany are ‘good looking and pleasant’, the women in Lyons are some of ‘the most beautiful in France’, the women in Normandy and Picardy are ‘ugly’, and that the women in the Riviera are ‘as plain as can be’. You know, all the vital details that a Cardinal would like to recall about his trip.

Editors of the modern translations of the journal mention that there was nothing ‘professionally celibate’ about the Cardinal’s visits and likewise, his personal life. For example, in November 1517, they attend a public banquet in Avignon, Beatis writes:

“Many beautiful ladies were present, and after dinner there was dancing until midnight with unconstrained merrymaking and diversions.”

Ah, to be a rich Cardinal during the Renaissance, huh? That would be the life.

And so it is thanks to Beatis and Monsignor Cardinal that we also have the first written account of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

On July 30th, 1517, the Cardinal’s tour of indulgence brought them to the palace of Henry the III, Count of Nassau, in Brussels.

Henry the III was known for his enthusiastic support of the Renaissance, both as an intellectual and artistic revival. He was a frequent patron of the arts and a collector of many wondrous artworks which he would fill the guest rooms of his palace with.

When Beatis and Cardinal d’Aragona meet with Henry the III, they were given a tour of the estate and its galleries. They would have seen exquisite and rare jewels in Henry’s collection, the meteorite on the lush garden grounds, countless paintings of nude figures from modern Renaissance artists, including a notable depiction of Heracles and Deianira.

They would have also been shown the guest room, where dinner guests, too drunk to leave the grounds could spend the night on an enormous bed, big enough for 50 people.

No doubt a moment for some passing wit from the Cardinal:

“And is this where you sleep your excellence?”

“Only on Saturdays your grace.”

Henry would have then shown them his prized painting…

A triptych altar piece by the infamous Netherlands painter: Hieronymus Bosch.

This was the pièce de ré·sis·tance. A work so massive, it towered over the Cardinal and his assistant. The work itself being seven feet tall and twelve feet wide. It stood on a raised platform, meant to emulate an altar, making it appear even more enormous to the viewers present.

The triptych is painted on three oak wood panels, attached with hinges, so the work can be open or closed. Traditionally, triptych altar pieces would remain closed, except for holidays and Saint Days. Meaning that the opening of such a massive work is a spectacle in itself.

At this moment, the panels were closed. On the exterior shutters, Bosch painted a depiction of God creating the Earth. The scene is depicted in a limited color range of black, white, grays, and browns. During the Renaissance, this style of painting is known as grisaille, and it is meant to give this ancient look, something that looks like sculpture.

The painting on the exterior of the triptych is known as The Creation of the World. It shows a large glasslike orb, in which clouds and a landscape of vegetation can be seen. In the foreground of the landscape, on the left panel, you can see strange structures which look like claws and there are some other objects behind it on the left which have stems. These are odd fantastical elements common in Bosch’s landscapes. They are abstractions of nature’s forms.

Aside from the vegetation, the landscape looks lifeless, an effect further enhanced by the foggy grayness of it all. It is assumed that we are seeing the Creation of Earth on the Third Day, the moment God introduces water. It looks as though the bottom half of the orb, under the land, is filled with water.

If you look closely, on the upper left, you’ll see a figure of God the Father, with a beard and a golden crown on his head, and a Bible in his lap. According to the art historian, Hans Belting, God appears hesitant and morose, not majestic and all powerful “as though the world he had created was already slipping beyond his control”.

Above God, Bosch has inscribed a verse from Psalm 33 in Latin, it says: “For he spake and it was done; he commanded and it stood fast.”

This representation of the world as a glass orb can be seen in medieval and Renaissance paintings. Often it is held in Jesus’ left hand. It is a symbol of the Earth.

Bosch’s painting of the third day of creation, is beautiful alone, and would have left a unique impression on the Cardinal and his assistant. But at this moment, Henry the III would have said “Just wait until you see the inside.” And signaled to his servants to open the panels.

[cue music]

As they did so, the effect would be like watching a massive flower blooming. The anticipation of what could be inside, paired with the explosion of rich colors, gradually revealing the interior, and stretching outward for twelve feet. A moment of strange awe and wonder.

Beatis writes about it in his notes, saying:

“Then there are various panels with diverse fancies where there are represented seas, skies, woods and fields with many other things; some who come out of a seashell, others who defecate cranes, men and women, both white and black in various actions and positions, birds and animals of every kind and executed with much truth to nature, things so pleasing and fantastic that it is quite impossible to describe them to those who have not seen them.”

The panels, forming an open doorway, invite you in. A visual feast of greens, blues, and pinks washes over you. The oil paint has an otherworldly radiance, due to its bright colors and its application on oak wood.

The experience of The Garden of Earthly Delights is divided into three sections. A left panel, a central panel, and a right panel. When standing before this work, people of the late medieval period, would expect a triptych like this to depict Christ’s crucifixion in the central panel, and representations of donors or Saints in the side panels.

But here is Bosch’s first innovation. Rather than meeting you with a dramatic crucifixion, you are met with a scene of decadent splendor, countless naked men and women embracing, feeding each other, and even bathing. Not only that, there are also animals, many of which appear in strange proportions to their human counterparts: an oversized owl, a gigantic duck, a clamshell the size of a man.

Then your eyes dart across the piece, to the right panel, where your attention is drawn to an immense blackness… Severed ears with a knife emerging from between them, a nude man being stabbed by a demonic animal, a knight being eaten alive by strange rats…

What in the hell is going on here?

In your confusion, if you zoom your attention out again, you will see that the three panels are meant to be seen from left-to-right. They tell a story of sorts…or convey a lesson.

In the leftmost panel, we see the Garden of Eden…Paradise. With the commanding image of God standing between Adam and Eve.

In the central panel, we see the Garden of Earthly Delights.

And in the rightmost panel, we see Hell. This is arguably the most inspired and creative vision of Hell which has ever been painted.

I’ve stared at all three of these panels…for hours now. And there is so much to say about each one of them, that it’s difficult to find a place to start. The entire artwork becomes like a kind of medieval mandala. It is meant to be stared at and reflected on. And like a mandala, it’s a densely populated web of puzzling imagery which challenges you at every turn. Even after staring at it for hours, you still find things that surprise you!

When I first started research for this episode I thought “Well, the Garden of Earthly Delights, right, I’ve heard of that. This will be easy…” But no. I really had no idea. When I started looking at the painting, none of this made sense. In trying to see meaning in it, you are basically overwhelmed.

There are few paintings which continually challenge you the way The Garden of Earthly Delights does. And this is part of what makes it a great work. Bosch doesn’t just paint intriguing things for us, it becomes clear that he knows how to command our attention. And this is why he is a master of the Renaissance.

This piece belongs to a longstanding tradition of late-medieval triptychs, meant to serve as altar pieces. The triptych, as an art form, is more than just a pretty picture which decorates an altar. It has a very real functional purpose.

During the medieval period, many of the parishioners of a church could not read or write. One of the most common figures that appears in Bosch’s paintings is the peasant. And this is partially because he was accustomed to peasants and farmers being his main audience in the town of ’s-Hertegenbosch. The working class, at this point in history, did not need to know how to read and write. But they did need to know what moral and spiritual lessons should be guiding their daily life.

And so, during the medieval period, up until the start of the 1400’s, that was largely the function of public art. It embodied the lessons which were taught in the churches. And as a good Christian spent time in a cathedral, they would pause and reflect on the imagery before them. Symbolic imagery which helped crystallize those moral and spiritual lessons.

As a priest gave a sermon, he could point to a specific painting or altar piece, and its imagery would help the congregation visualize the story being conveyed–and to internalize it. Art served a very real function. It wasn’t just aesthetics.

And this is the tradition which Hieronymus Bosch was born into. This is how his father, his grandfather, and his great-grandfather viewed art. There were no art galleries, the local cathedral was a town’s art gallery.

We need to view The Garden of Earthly Delights from this perspective, to truly appreciate its genius. All the seemingly bizarre symbolism begins to make sense when we understand the time, place, and purpose of its creation.

[cue music]

A churchgoer of the 1500’s would understand that this type of triptych is meant to be viewed from left-to-right. Instead of showing Christ’s crucifixion, it presents the viewer with a narrative that communicates a moral lesson.

We’ll begin our deeper dive into the garden by exploring each panel in order.

Panel 1: The Garden of Eden / Paradise.

In the first panel, Bosch shows us a scene from the Garden of Eden. The moments after Eve has been created from Adam’s rib, and God is presenting her to Adam.

Adam is on the left, he is nude, and reclining on the grass, with his right arm propping himself up, looking in God’s direction. God is in the center between them, with his right hand in a symbol of Benediction. This is a traditional Catholic gesture denoting a blessing being made.

God is shown here in a light red flowing robe. And his youthfulness seems to imply not God the Father, who we see represented on the exterior panels, but God the Son, in his Jesus role. This is a deliberate choice made by Bosch. But why?

We see the God the Son figure holding Eve’s right wrist, with his left hand. She is nude like Adam, but she appears to be floating in midair, as if she has just been created. There is an elegance and grace to her pose. Her eyes are downcast, denoting a submissiveness or introspection.

Notice her long and flowing hair, which has a beautiful golden shimmer, and which extends all the way down past her hips.

There is no doubt that Bosch has painted Eve to fit within the beauty ideals of Netherlands during the late 1400’s. Bosch has made sure she is beautiful, because what happens next in the story needs to be believable.

The viewers of this painting, in Bosch’s time, need to see Eve as desirable. Why? Because Adam sees Eve as desirable.

Look closely at Adam’s face. Specifically his gaze. Despite God’s presence before him, Adam’s line of sight is focused on Eve. He looks directly at her downcast eyes, with a certain excitement. Notice the subtle red flush on his cheeks. Which is absent from Eve’s.

Adam has found the object of his desire. We are seeing depicted… the origin of Lust. Adam is turning his attention away from God, and fixing it on Eve. This is The Original Sin which will cast Adam and Eve out of Paradise.

Bosch has given us several details to drive this message home. Notice to the right of Eve, near her feet, are two bunnies, near their rabbit hole. And we all know what bunnies do in rabbit holes.

Next, notice the incredible tree to the left of Adam. With these beautifully rendered grape vines climbing up. It’s a distinctly exotic looking tree. Not like any tree one would find in Den Bosch, where Bosch lived all of his life.

After doing some digging, I found out that this is called a Dragon Blood Tree. And it is local to Yemen near the Arabian Sea. It was around this time, in the late 1400’s, that travelers begin to document and even bring back plant life from other regions of the world. And this is likely how Bosch came to know this tree. But why does he feel inclined to paint it here? Depicted with such great care near this pivotal scene?

It turns out that the Dragon Blood tree gets its name from what happens when you cut its bark… it bleeds. And the liquid it bleeds is blood red. Bosch has placed the Dragon Blood tree in this scene as a symbol. A foreshadowing of what’s to come.

As the Christian myth tells us, the Son of God has to be crucified for the Sins of Man. It’s Jesus’ blood which will have to be spilled, which is also here represented by the grape vine climbing its way up the Dragon Blood tree. Notice how the leaves of this vine are carefully painted by Bosch to resemble discs. The play of light on these discs is really exquisite. Scholars theorize that they represent Communion wafers.

This vine stretches up the Dragon Blood tree to its branches, whose leaves, at their peak, resemble crowns.

And this is likely the reason why Bosch chose to represent God in his Jesus form, as a foreshadowing of the sacrifice that will be made.

One final detail to notice in Bosch’s portrayal of this scene is the way Adam’s legs extend, to touch God’s right foot. And how God’s left hand clasps Eve’s right wrist. All creating a kind of metaphysical circuit that connects all three.

Although the rest of this panel depicts the Garden of Eden, there are already signs that all is not well in Paradise.

At the base of this panel, right near Eve and God’s feet, is a dark pool of water. A pond, which is filled by a black shadow, the shadow seems to come from beneath the water, an odd effect, and from which, dark animals are emerging, large birds, a rooster, a seal, frogs, and odd chimera-like creatures. In the medieval period, chimeras were often seen as symbols of evil. Unnatural creatures, fused from multiple parts. So what are they doing here? In Paradise?

You see swimming in this black pool, a fish with a platypus head, another with a black unicorn’s head, a fish with wings, another with a rooster’s head. All in these startling dark colorless forms. They create such a contrast to the lively greens and blues in the rest of the panel.

This confused the hell out of me… I stared… and stared… and then I realized… this black in the first panel…it appears elsewhere… it’s echoing the last panel… The dominant color of Hell is BLACK. The heaviest and densest black possible. Of course, it makes sense.

Adam and Eve are symbolically standing on the precipice of Hell, right at their feet.

It felt like this insight was getting me closer to the answer. But something about all these animals still made no sense… Then, I was staring at one in particular… this elegant three headed bird, with brownish gold feathers. Resembling something like a peacock phoenix… Three heads. Is Bosch referencing the Trinity?

It looks like this peacock phoenix is fighting or arguing with the other animals. His beaks are open, as if ready to snap, and two of the heads are directed down into the shadow pool, one snapping at the black unicorn fish, the other at the black platypus fish. What the hell is going on here?

Are any other animals fighting?

On the bottom left corner of the panel… a fantastical bird, with its tail feathers up is snapping at a black shadow creature, which resembles a similar bird with a reptile tail.

Then, just above them, you can see a tiger cub, carrying off some kind of black reptile in its jaw. Of course! The animals which are predominantly black… are not from the Garden. They don’t belong in Paradise… they have emerged from the black pool, whose shadow is Hell’s doorway.

I haven’t seen or heard anyone discuss this aspect of the animal symbolism. But it seems so obvious now.

All the animals which are in color, and not black, belong in Paradise. The rest, are shadow creatures, upsetting the balance. Following this thread of insight…the bunnies near Eve’s feet begin to make more sense as well. They are not white, or brown, or gold… they are black bunnies. Whose home is a shadowy hole in the ground.

It’s a deeply symbolic scene. We are witnessing the crack in the pearl. The moment a corruption enters the Garden of Eden.

The question is: does Adam’s lust invite the corruption? Or does the corruption cause Adam’s lust?

Looking further up in the panel, directly above and behind God, we see a blue pool of water. With an ornate pink fountain. According to historical documents, Bosch likely modeled this fountain after a baptismal font, that was installed in his local Saint John’s cathedral in 1490, shortly before he began working on this painting. This was a cathedral in which he attended Mass often, and in which the fraternity he was a member in, called The Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady had their own chapel.

This is a fountain of life giving waters. In Genesis 2:10 it reads: “A river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it parted and became four river heads.”

[cue music]

But even here, at this pink fountain, something is off. The blue at its base seems to grow a dark azure hue. And its rocky base is littered with black stones and glass tubes. To the right of the rocky base is a black toad, sitting atop a rock, looking toward other animals. Emerging from the water, onto the dry land, are more shadow creatures… Black reptiles, enormous tadpoles, shelled chimeras, and an iguana with three snake heads.

They seem to be headed in the direction of a small dark cave, which enters into the barren rocks. Growing atop these sandy colored rocks is a fruit bearing tree, with a black serpent wrapped around it. Is this the serpent that will soon tempt Eve? After it has just slithered out of the Hell’s shadowy abyss?

One can make the argument that this paradoxical corner is the beginning of surrealism. Let me explain…

Notice how the sharp protruding angle of the rock face forms a nose. The coiling serpent underneath forms the lips. The black and blue shelled beetle forms the eye, with its seven legs being the eyelashes. Bosch has made a literal ‘rock face’. He has painted something fit for a Salvador Dali painting, 500 years ahead of his time.

Out of this rock face, a symbolic Tree of Knowledge grows from its forehead.

Does that make the dark cavern of the ‘ear of man’? Into which Hell’s shadow creatures enter as whispers.

Heavy stuff…

[end music]

The animals behind and above the fountain seem to be oblivious to the corruption. It has not reached them yet. Some drink from the water’s edge on the left, including white heron, cattle, deer, and a white unicorn.

But on the far right, slightly above the serpent entwined tree, a black boar with her young, marches onto the scene. Bearing her teeth, and threatening a mongoose-like creature, that escapes from the boar, hissing back at it with open jaw.

In the background, in the topmost section of the panel, we see a blue landscape. Decorated with the features that we saw on the exterior panels. These aren’t natural hills or rock formations that someone like Leonardo da Vinci would paint, these are abstractions of nature. A signature Boschian landscape.

One final indication that all is not well in Paradise… occurs at the exact center of this first panel. It is positioned so precisely that one must assume Bosch measured the height and width and planned his composition around it.

If we look again at the pink life giving fountain. There is a shadowy hole in the center of the circular base of fountain. Perched right inside of that hole, is an owl, with piercing yellow and black eyes. He seems to be gazing intensely at something outside our view. Either he gazes into the dark depths of the water, or tracing his line of sight, he seems to be gazing at Adam… or the Dragon Blood tree? Or is he gazing at us?

This ominous owl is a recurring symbol in Bosch’s paintings. It is nearly always hiding somewhere in the shadows. Ominously watching the events unfold. Is it the eye of God–always watching? Or is it the presence of evil? Satan himself?

Whatever the case… Bosch has taken great care to place this owl… encircled in black, in the exact center of the Paradise panel, inside of the baptismal font. As if to say… ‘Here is the cause of the corruption.’

And in a stroke of sheer genius, or an accident approximating a miraculous coincidence… The owl appears perched on a crescent moon. This effect is achieved by the perspective we are viewing the opening of the fountain from, on which the owl is perched. As the circle hole slightly reveals its inner wall, the effect of a crescent moon is created. If this was intentional, it’s a stroke of symbolic genius.

The crescent moon is a symbol Bosch includes in other paintings, especially on flags, such as in his painting, Ecce Homo, in which context it is synonymous with man’s evil doings. Is it a coincidence that the ominous owl is perched on the crescent here? As a kind of Easter Egg? Considering Bosch’s clear mastery of symbolism, I think he knew exactly what he was doing.

Panel 2: The Garden of Earthly Delights / The False Paradise.

The central panel of Bosch’s triptych is known as The Garden of Earthly Delights. And although we don’t know what Bosch named it, in the centuries following his death, art historians settled on this title for it, and due to this central panel’s reputation and the countless debates that followed, the name ended up referring to the entire triptych itself.

Any casual attempt to make sense of this masterpiece…fails miserably. And it’s not just you. This thing has baffled scholars and historians for centuries.

Every new generation casts its own interpretation on it.

Part of the reason for this is the sheer quantity of forms and scenes and symbols that Bosch is using. In even letting your eyes wander through it for five minutes, you begin to feel overwhelmed. There is just so much going on. On examining it my first time, I remember my eye darting from scene to scene, from one group of humans to another, from animal to animal, and fruit to fruit, in a never ending cycle of fascination. I felt like a hummingbird checking every flower.

It’s as if your mind is looking for a key of some kind, something that will give it the context you are looking for, the missing piece that will bring it all together.

Part of what gives this central panel its overwhelming busyness is the sheer number of bodies. They seem to never end… that is, until you count them all. Which I did, of course.

It sounds improbable, but after googling ‘how many people are in the Garden of Earthly Delights?’…Nothing came up. So I had to count them myself. So how many people do you think are in the central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights?

In the central panel alone, there are over 500 people.

Yeah. I know. And that’s why it’s so overwhelming.

Our vision is so tuned to seeing people and quickly forming an insight about them based on their facial expression, their body position, and their relationship to people around them… That in letting your eyes wander this painting, your mind goes into overdrive… Trying to understand what 500 people, in their countless groups and subgroups are up to.

But as much as it’s baffled everyone else for centuries. We are going to make sense of it.

To get a better grasp on it. Let’s first think of this painting as divided into four planes of action. The Foreground, the Mid-Foreground, the Middle Ground, and the Background.

The Foreground includes the tallest figures at the base of the painting. The Mid-Foreground includes the figures just above them, who seem 2/3rds their size, this area roughly starts with the couple in the orb on the left hand side, and goes across the middle, with its upper limit defined by the first bushes that run across the middle. The Middle Ground is largely made up of the procession of animals and people around the pool. And the Background includes the monolith structures and everything behind them.

So what’s happening here?

Well, in the most general sense, each plane of action shows people engaging in different behaviors, all being performed by naked humans. In the Foreground and Mid-Foreground, we see nude humans playfully interacting with one another in small groups. The groups range from two people to six people to fifteen people and everything in between.

Most of them are smiling, laughing, and generally having a good time. This is the party of the century, and everyone’s invited.

There’s even two who are seemingly dancing, forming the shape of some pagan godhead with four legs, four arms, a flower bud body, and an owl for a head. In their hands, they hold big ripe red cherries. And this forms a primary theme of these naughty revelers…they are all interacting with fruit.

From red cherries and red strawberries, to blue grapes and fruit-like shells which the people are playing in and around. Some are climbing into them. Some are breaking out of them. And some are… I don’t know what this one’s doing… drowning himself upside down in the water while balancing a red fruit shell on his perineum.

A majority of these revelers are eating the fruit, or feeding the fruit to someone. And there is a certain intimacy in the way they are often touching each other. For some, their desire isn’t the food, but the other person.

It gives the impression that the theme of these two first planes of action in the painting is appetite. The desire to eat, to partake, to fulfill, to satiate, and be satisfied.

Among these revelers are animals. But aside from two big fish and a butterfly, all the animals in the Foreground and Mid-Foreground are birds. There are roughly 16. Many of them are enormous, and out of proportion from their natural size. Three of these are feeding humans, who are seemingly entranced, or in a state of submission.

One interpretation, put forward by some writers, is that this central panel represents an idyllic world. One free from sin. Free from Judgement. Where man is one with nature.

In the 1960’s, this central panel was interpreted as capturing the ‘free love’ spirit of the 60’s. This is the first Woodstock. And the surrealist quality was explained by the possibility of Bosch partaking in hallucinogenic drugs. They certainly look to be having a good time.

Other art historians argue that Bosch is representing what happened after Adam and Eve were kicked out of paradise, as in the first panel, but just before the Great Flood occurred.

During Bosch’s time, this time period was considered a very real historical period of human history. Is Bosch showing us his visualization of humanity before the Biblical Great Flood?

Referencing the Bible, we find this passage in Genesis 6:1:

“Now it came to pass, when men began to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born to them, that the sons of God saw the daughters of men, that they were beautiful; and they took wives for themselves of all whom they chose.

And the Lord said, ‘My Spirit shall not strive with man forever, for he is indeed flesh; yet his days shall be one hundred and twenty years.’

There were giants on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in, to the daughters of men and they bore children to them. Those were the mighty men who were old, men of renown. Then the Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every intent of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.”

Then in Matthew 24:37, we further read:

“But as the days of Noah were, so also will the coming of the Son of Man be. For as in the days before the flood, they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day that Noah entered the ark and did not know until the flood came and took them all away, so also will the coming of the Son of Man be.”

There is no doubt that Bosch studied the Bible, and knew these verses well. When we explore his other paintings, we notice he often creates visualizations of passing phrases from the Bible. Is that what he is doing here?

The impression that this central panel has on me, now that I have stared at it for hours, is that all of these revelers have given in to their animal impulses. The impulses have grown larger than the human virtues. And in a sense, they are without sin, because they have entered into a primal state. The passing pleasures have driven them to a point where they have lost their higher thought and self control.

Is there any evidence of this in the painting? Or perhaps any indication that things are not what they seem?

Some of the symbolism seems to indicate that the order of the world is out of balance. For example, the man upside down in the water, on the left, balancing a fruit shell between his legs. Is he drowning in lust? Perhaps a visual metaphor for the phrase: the world is on its head.

Then animals feeding humans, as if they were their pets. Of course, the argument can be made that this is symbolic of man’s harmony with nature, and I can see that interpretation working as well.

But in the most disturbing display, which is located in the leftmost pool of water. We see a man, restraining a woman’s wrist with his right arm, while embracing her, and drawing her closer with his left arm, which is around her back. She doesn’t seem in distress… but the man is turning his attention away from her, as if momentarily distracted, as if he is peering back at us. With a look of concern.

Have we walked in on something? Which we were not supposed to see?

A hint that perhaps…all is not well here.

Behind him we see an enormous bird, feeding grapes to three humans, who are contorting themselves to reach them. The bird is a European Goldfinch.

Bosch has painted these three men in strange sickly grey tones–as if they are half dead. They give the impression of addicts in withdrawal. Some scholars say these grapes and these sickly figures represent the corruptions of the church, as grapes are associated with Jesus, and the blood of Christ. But I’m not so sure about that interpretation.

One thing is for sure though…this contrast, between the man restraining the woman, who seems to stare blankly at the enormous bird behind them, and the discolored panicked men… lends an unsettling feeling. The world has run amok.

Immediately to the left of this, there is a Kingfisher bird, which Bosch has rendered to beautiful effect. From all the humongous birds, it’s perched closest to us, and sits on the back of a male mallard duck. It is interesting to note that the Kingfisher is a bird known for one incredible talent…it hunts fish right out of the water. It waits in the trees and when it sees its moment, swoops down with intense speed, and pierces a fish with its beak, then flies back out and eats it.

It’s interesting to note that Jesus’ symbol is the fish. So not only are these larger than life birds symbolizing the sway of our animal impulses, and the subservience of lustful man to nature, but also, in this case, the symbolic death of Christ, a theme which Bosch takes great care in foreshadowing in Panel 1, which we discussed earlier.

Directly below this Kingfisher, we again see Bosch’s favorite recurring symbol… the owl. Here it stares back at us with pitch black eyes, as a man embraces it, extending his hands, looking at us as if to say ‘Here he is! Our favorite pal.’

A second owl appears on a perfect horizontal axis across this panel on the right side. The two owls acting like columns, enclosing the painting.

Recall that in Panel 1, it’s the ominous owl perched in the shadowy hole of the baptismal fountain, which may be the cause of the corruption.

Nearby, there is one of the most beautiful scenes from the entire triptych… A man and a woman in close intimacy, with their hands on each other’s thighs, the man is leaning in to kiss the woman, whose hair is as long as Eve’s from the first panel.

I haven’t seen any books discuss this next point.

They are seemingly floating in an orb formed from some transparent membrane, and its color and shape seems to be a visual echo of the orb on the exterior panels, of God’s creation of the world on the third day.

As if to say, each act of sex contains within it some remnant of that first creation of the world. We have to give Bosch the benefit of the doubt here, that this was his intention, he has proven time and again to us already that he is a master of symbolism.

But even here, notice something is ever so slightly off. This gorgeous orb is connected by a curved stem, to a hollow fruit shell in which a man is peaking out, looking through a glass tube. At the entrance of the glass tube, there is a black rat. Perhaps planning to make his was into the fruit, to eat it.

It’s important to note that Bosch was born around 1450, roughly one hundred years after the Black Plague. A bubonic plague which decimated Europe and Africa in the mid-1300’s, killing millions of people in less than a decade. It was a catastrophic event of human history. The plague leveled societies, without regard to wealth or nobility, age or royal status.

It even killed those who were most aligned with God, the priests, with particular cruelty. As many priests and monks would attempt to care for the sick, they would quickly catch the black plague, and die equally torturous deaths.

Humans of the time didn’t know anything about bacteria, but the association between rats and the black plague did form an impression about rats being filthy or disease ridden creatures. And this impression continues to echo in our collective unconscious centuries later.

Although animal lovers will tell you the contrary is true. And that rats clean themselves even more frequently and thoroughly than cats. But ideas and superstitions have a life of their own. Just as wolves are thought to be the most dangerous beasts of the wilderness, according to folk tales we tell. Yet in truth, they just want to be left alone. Rats have a specific association in symbolism.

Bosch would have definitely learned about the horrors of the Black Plague. And to include even this singular black rat attempting to enter the fruit of lust is meaningful. He is here to spoil the party. Bringing with him the symbolic association of uncleanliness and the plague, which undoubtedly many Christians saw as God’s wrath for humanity’s sinful ways.

Let’s return to the Riddle of the Garden: is this an innocent paradise or a sinful false paradise?

With that question in mind, I’d like to call your attention to something surprising I noticed in the painting. Something which in any other context in the highly religious atmosphere of the late 1400’s would have been… completely controversial.

Homoerotic love.

There are at least three examples of it in this central panel. Remember that this is during a time when many cities, such as Florence, had sodomy laws, which punished men who engaged in sexual activities with other men.

First, on the lower left, near the black skinned woman, there is a pink fruit shell that resembles a pumpkin. Out of the bottom, there is a glass tube pointing outward toward the ground, a man looks at us through it, from inside the fruit, with his hand on his chin, and a smirk on his face. The other half of his body, hangs out of the broken bottom of the large fruit shell.

Now, I haven’t seen any historians thoroughly analyze this next part I noticed.

Still at this large pink shell, directly above the man laying down, two men are about to kiss. One is emerging from an opening in the top of the shell, with his fingers gently reaching out for another man’s chin, and this other man is bending down at his waist to meet him.

Finally, right next to them, standing behind the pink shell, three men are gathered intimately close to one another, making eye contact with each other. The man who is lowest holds a blue flower to his heart, the man behind him rests his left hand on this man’s shoulder, and the one in front of them, with his back to us, is grabbing the thorny stem of a plant with his left hand which is emerging from the opening of the pink shell, and he carries a massive strawberry on his back, the spiny stem of which curves downward and appears to be entering his butt cheeks with a blue flower on its end.

It’s hard to say that this arrangement of symbolism is coincidental, as this stem gripping man with a strawberry (the painting’s fruit of desire) extending into his backside, is positioned as part of the group that includes a man about to kiss another man.

The second example of homoeroticism, is less overt, but equally suggestive, and again, no one talks about it. It occurs at the bottom of the painting, just right of center, in the foreground.

A man is on his knees, bending over in front of another man, who is reclining against a massive strawberry. The man in front, who is bending over, is leaning with his forearm against a large fruit which has burst open, and from which little blue and red fruits spill out, which he seems to watch with fascination. The man who is reclining is looking out at us, about to take a bite of a ripe red cherry in his left hand. Interestingly, the first man, who is in front of him, is positioned in such a way that it overlaps with this reclining man’s crotch. And it is like his attention is implied to be directing in that direction, but Bosch has overlaid this fruit to not be too overt.

And to add to it, the large red strawberry which the cherry eating man is reclining against is being greedily hugged by another man.

The third example making homoerotic commentary is directly above these three men. This third example has only two men, both on their knees. One is standing on his knees, holding red flowers up in his right hand, by the stem. His attention is directed downward to the right, where another man is on his knees and elbows, presenting his butt in the air…into which, the first man seems to have placed two flowers. A blue and a red one.

If we follow the thread of symbolism here, concerning the flowers, the two men, and the willing insertion of the flowers into this man’s rear end, when viewed in the context of the rest of the garden’s activities, this must allude to sodomy… right?

There was a Latin phrase known in the medieval period: Peccatum contra naturam. Meaning a ‘sin against nature’. During that time, homosexuality was argued as a sin against natural law. And this phrase was referenced in such arguments. This may be the explanation for Bosch’s choice of flowers, as symbols of nature, to create a visualization of that latin phrase.

One final thing to mention about these three scenes of homoeroticism… I hesitate to say the first two are negative depictions, because aside from the thorny stem in the first one, they have no negative symbolism. And the third one I would say is more satirical than it is negative.

It’s unclear whether Bosch intended these scenes as a criticism, but they remain significant either way. Because outside of depictions of St. Sebastian, these three miniature scenes in The Garden of Earthly Delights may be the only representations of deliberate homoeroticism in medieval and Renaissance art which were not at some point destroyed.

Let us now shift our attention to the Middle Ground and Background, and see if we might find an answer to our problem there: is this a depiction of true paradise or a false paradise?

[music]

In looking at the Middle Ground and Back Ground we should point out something which ties panels 1 and 2 together. If we zoom out and look at the three panels the way we would see them in person. We notice that Panel 1 and 2 are nearly identical in Bosch’s color choices. The dominant colors are this muted green of the grass, the cerulean blue of the sky, water, and distant landscape, and the unique fleshy pink of the fountains and monuments.

But even more than that, Bosch has created a relationship between Panel 1 and 2 through the background of the landscape. The distant blue horizon and the green hill in front of it fuse perfectly across the panels as if they are one and the same landscape. The intention seems clear, this is the same place but at a later date.

We can even associate the four rivers of the background with the four rivers of the Garden of Eden. Genesis 2:10 states: “A river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and there it divided and became four rivers.”

The middle plane of the painting is centered around a circular pool of water, in which naked women are bathing. Some with birds or fruits on their head. Circling around this blue pool is a procession of animals of every kind being ridden by humans. We see horses, deer, donkeys, goats, griffins, unicorns, camels, boars, bears, and cattle. The sheer variety of four legged animals is incredible.

On many of these groups of riders, we also see various birds, perched on people’s heads or on animal backs or horns.

I believe this is another instance of Bosch depicting man’s animalistic impulses. Of wild, untamed desire, as it parades round and round with no aim or purpose, except its own pleasure. Some of the riders seem to be flailing backward, overwhelmed by their feverish state.

In another example of Bosch’s incredible sense of humor, one of the riders even stands on one leg, on the back of a moving horse, and he is flipping himself upside down, while his other leg is extended, with his head looking back upward at his own penis. Or… is he looking up at the blue bird, seemingly poking his beak into the man’s butt cheeks?

One of the groups, on the right side, shows three men riding together, holding up a large blue fish, with a red fish tail hanging out of its mouth. A possible symbol of gluttony and overindulgence. On top of this engorged blue fish sits a black bunny.

Recall the other time we saw black bunnies was in Panel 1, at the feet of Eve. The moment Adam had turned his eyes away from God, when Lust had filled him, and the expulsion from Paradise was inevitable.

Bosch keeps calling us back to that moment, as if to say, all of this ripples outward from that Original Sin.

Three final details in this procession hammer this point home…

Notice that all of the riders on the animals are men. There is not a single woman. All the woman are instead in the pool, as the animals circle, in a counter-clockwise direction, perhaps another tell that things are off.

There was a white unicorn in Panel 1, drinking peacefully from the life giving waters in the Garden of Eden. Notice that here, in the procession in Panel 2, this white unicorn reappears, but its horn has grown three times in length, and jagged spikes have grown out of it. It’s worth noting that this white unicorn and the one in Panel 1 exist on the same horizontal axis. If you draw a straight line from left-to-right, the unicorns line up perfectly, as an almost ‘before’ and ‘after’ depiction.

There is one final detail about the procession which I haven’t seen scholars mention. And it is one which I found only when I was seriously debating the Riddle of the Garden: is this an idyllic innocent paradise or is this a sinful false paradise?

My attention was circling the procession of horses, donkeys, camels, and bears… when my eyes stumbled on an animal…that seems out of place. It doesn’t have a human on it, and it’s slightly out of the procession line…it is a spotted boar. Located at the lower right of the procession.

At that moment it hit me…like a bolt of lightning. This spotted boar, is the answer to the Riddle of The Garden. Look at its fleshy pink skin, this is the exact color of the fleshy pink monoliths in the background, a color which resembles the color of flushed skin. Then I noticed the engorged sex organ under the boar’s tale. It might be its testicles or it might be a vulva, but in either case, Bosch has painted this aroused organ cerulean blue.

The exact blue of the spherical monuments in the background. This is no coincidence. The blue monuments may be considered testicles or generative organs, the fleshy pink monoliths are either vaginas or they are arousal itself.

These structures, into and around which people climb, are the exteriorization of desire. As the spotted boar shows us, these are the embodiment of arousal. Its living space, its habitation… A closer look at the spotted boar only confirms this… See how the boar is turning its head, as if looking at its own arousal. Directing its attention back on itself.

And notice that rather than a human riding it, we see two cranes standing on its back. Likely a male and female, with their beaks open, calling out. Calling attention to the boar.

But the detail which brings it all together, and answers the riddle for us…is the one perched right above the boar, looking on. An owl.

The presence of evil. No longer in the shadows of the baptismal font. But out in the open air, looking down at the boar.

As in the first panel, there is also a baptismal font in this central panel. It is in the background, the same cerulean blue as the spotted boar’s sex organ. In the shadowy opening where we first saw the owl, we instead find a man reaching his hand between a woman’s legs, and near them, a bare ass displayed. Bosch is done with the metaphors, and drives his point home more firmly here.

We see people having sex in the baptismal waters. One man greedily gulps down the trickling water for himself. And we can see that the sacred structure appears to be cracking–it can’t hold much longer. Pretty soon it will burst, and what then? Will it flood the land with raging waters?

Desire has run amok in the phenomenal world, and all the humans have become seduced by its illusion.

[music]

On the next Creative Codex…

“Pack your bags. We’re going to hell!”

It’s time to explore one the most imaginative, entertaining, and disturbing visions of Hell in all of Western art: the third panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

During our journey through Hell, we’ll explore the deeply symbolic punishments Bosch devises for us, we’ll uncover the strange patterns that link all three panels together, we will also talk about the infamous butt music from Hell, delve more into the mysterious life of Bosch, and we’ll see how Bosch depicts Hell and human folly in his other paintings.

All this and more on Part 2 of the Hieronymus Bosch series.”

PATREON

Become a patron of the show, and gain access to all the exclusive Creativity Tip episodes, as well as episode exclusives. Just click the button or head over to: https://www.patreon.com/mjdorian

Wanna buy me a coffee?

This show runs on Arabica beans. You can buy me my next cup or drop me a tip on the Creative Codex Venmo Page: https://venmo.com/code?user_id=3235189073379328069&created=1629912019.203193&printed=1